Waste Not, Want Not

Let's use trash to learn about power and weakness

This is the beginning the second volume of Pocket Observation, a free curriculum designed to help you reclaim your attention.

In Volume 2, I'm sharing four pocket studies about trash cans, power that sorts us apart and the weakness that discards nothing. I'll be sending out one a week, in addition to our regular pocket notes about other stuff.

The pocket studies will use trash cans to consider the American pronatalist movement, a threat to reproductive rights, the origins of consumer culture, and meaning-making from scraps. That sounds like a lot now that I’ve typed it out. But I’ve kept each pocket study short enough to fit in a little pocket of time.

In this installment I share:

- a letter about shame

- an incomplete photo album of some things that went rotten and some things that kept

- a recommended reading list

You can follow along right here in the newsletter. Every study will be delivered to your inbox! You can also enroll for free at Pocket Observation, where you can keep a digital pocket observation log, access past Pocket Observations, additional audio notes, video, art downloads, and recommended resources.

This is all offered for free through a Creative Commons license. Want to support my work? Consider donating!

Reclaim your attention.

Dear Observer,

I didn't used to pay attention to trash cans. That changed shortly after I turned thirty. We’d just moved to Oakland. The walls of our rental were laced with mold. My husband ate all his meals at his office in San Francisco. I ate alone with the kids, reading picture books through dinner because I'd run out of words. We couldn’t pay all our bills. I still thought the tech industry was an engine of abundance - it just hadn't warmed up yet.

One lonely dawn, I heard a rustling outside. I looked out the window. An older woman was picking through our recycling bin. She wore an apron and long rubber gloves, her hair gathered neatly under a wide-brimmed hat. She pulled empty cans, jars and bottles from our bin and placed them gently into a folding shopping cart. I moved away from the window, worried I’d intruded into a moment that was not mine to witness.

Later, I’d recognize this as one of the moments that deconstructed my reality - the one framed by American individualism and the LDS Church. Why this moment? I don’t know. Of course, I’d always been aware of the way people in America are forced live on the margins of the formal economy. I’d been raised to understand that everyone a few circumstances away from asking for money on the side of the road. There but for luck go all of us.

But at the time, I mostly felt embarrassed. This woman had to dig through our discards. There might have been broken glass in the bin. Were her gloves thick enough to keep her from being cut? I hadn’t washed the spaghetti sauce from the jars, the stickiness off the cans. I couldn’t bear the thought of her gloves getting slippery with our mess.

I started rinsing out anything that could be redeemed for cash. I’d put our valuable recyclables in a paper bag on top of our recycling bin. I felt embarrassed about this too. Like I was still intruding. And I felt I hadn't done enough to justify my intrusion. When we had extra cash, I put it in an envelope and clipped it to the outside of the bag. This made me feel the kind of shame that filled my throat with acid.

If you’d asked me why I felt ashamed, I couldn’t have told you. I still thought authority was a natural formation. I didn’t understand that American social order was a system of domination. I thought the past was in the past. I thought the future was inevitable. I thought everything always got better for everyone.I didn't have the words for what I'd begun to learn about power. But now I do.

These words didn’t spring fully formed from the aether. They unfurled slowly, from heaps of years, experience and study. I’ve built a reading list of articles, blogs and books. I’ll send the list out in pieces, along with my pocket studies. Consider supporting the writers and thinkers I recommend with a donation, book purchase or by sharing their work.

The first pocket study will be sent out this week, along with digital ephemera and prompts for your own pocket studies. You can also follow along at Pocket Observation, where you can keep a digital pocket observation log, access past Pocket Observations, additional audio notes, video, art downloads, and recommended resources. (It’s all free. If that wasn’t clear yet!)

Don’t have time to pay attention to this right now? Don’t worry. It will keep. You can always access Pocket Observations right here.

At the end of the four weeks, I’ll send out a downloadable zine version of this Pocket Observation. You can print it out, mark it up, put it on a shelf. When the zine has lost its use, you can take it apart, use the paper to make bookmarks, wrap plates before a move. My writing recycled in service of your everyday life is the best thing I can imagine, if I am being honest.

Love,

Meg

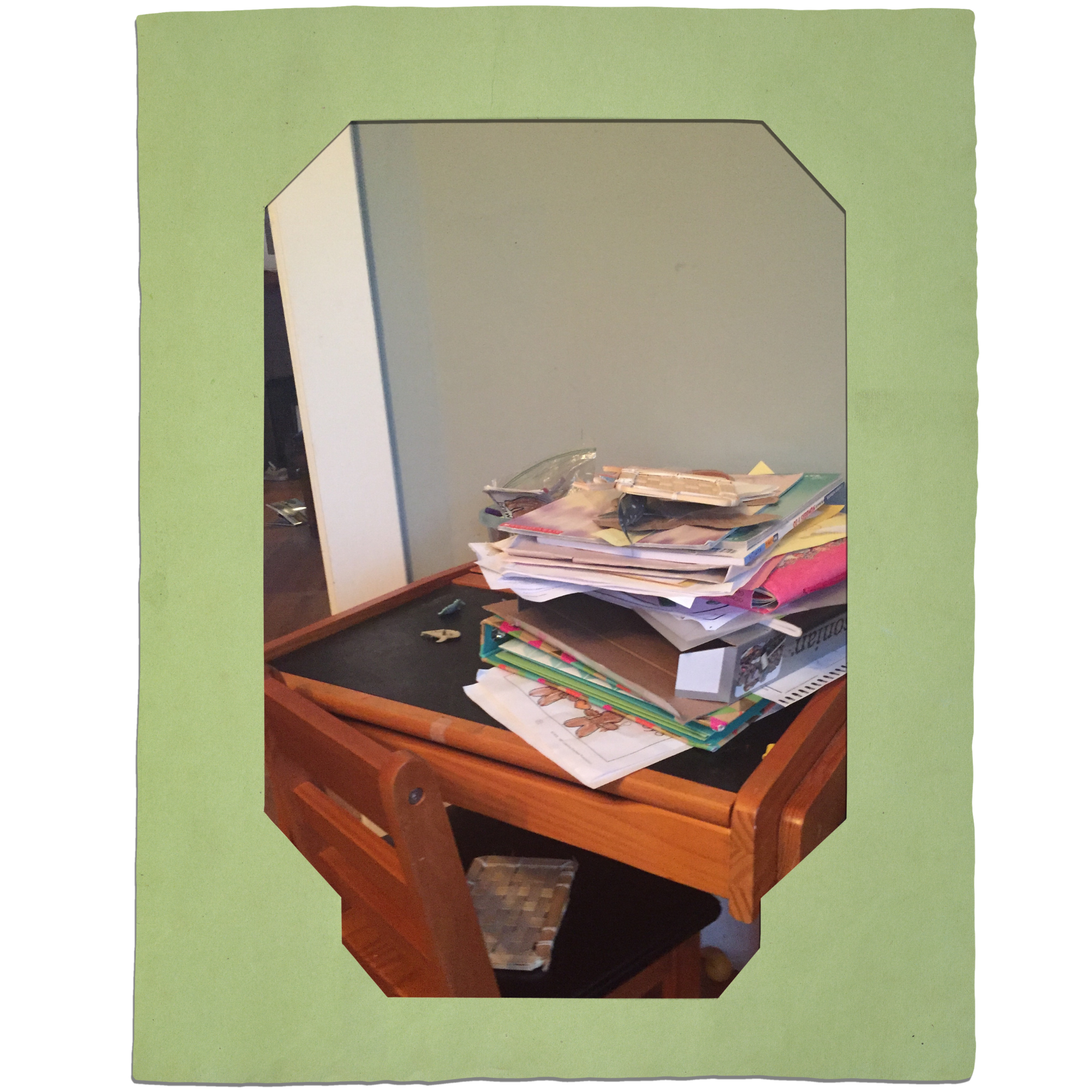

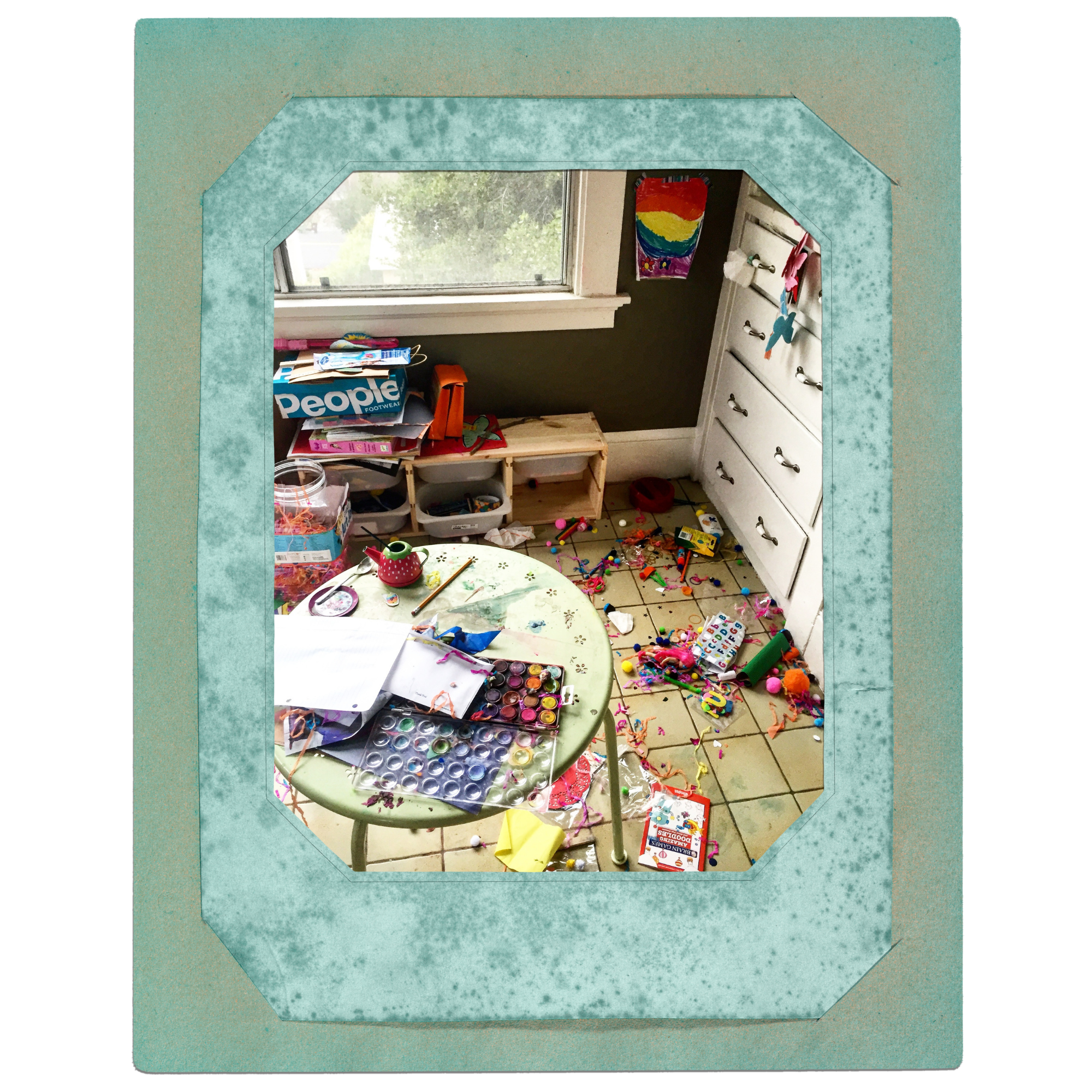

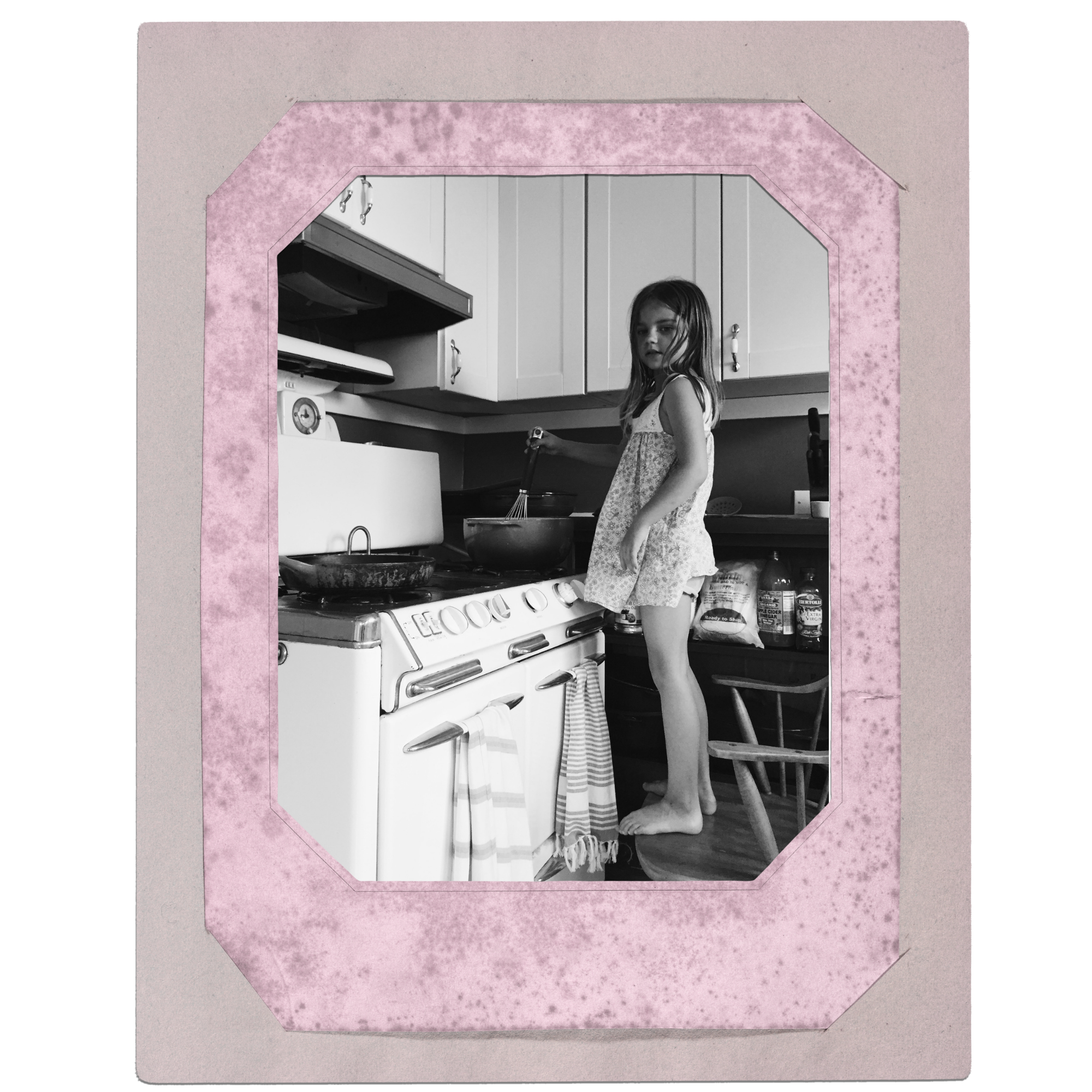

A few photos from our first year in Oakland, 2015

When I look through the thousands of photos I took during our years in Oakland, I can see I was seeing things I did not know how to name.

There are so many photos of the dinners I spent alone with the kids. (We were there together. But I knew they were too young to remember it. And no one else saw it happen.)

I unintentionally created an ongoing series of photos of piles of unscraped dishes, unsorted papers, rotting vegetables and wilted flowers. (What was I supposed to do with all the waste of our lives? And wasn't it my fault there was waste in the first place?)

Capture after capture of toys left on sills, in halls and strung from banisters. (Why was I the only one witnessing these little domestic moments? I was afraid of missing a single one. And also afraid of never missing a single one.)

So many blurred photos through the front window. (I was looking out them, alone. My husband usually got home after the kids went to bed.)

I didn't really grasp what I was trying to express. But I can see the images now as a project. I was unintentionally documenting my creeping understanding of how traditional gender roles and American Individualism manufacture isolation.

Related Reading from Pocket Observatory

A few pieces of context

I grew up in a mixed reality an environment where elements of virtual worlds and the real world are combined. My virtual world was formed by my religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. After a failed 19th-century attempt to maintain a theocracy with physical borders, my Church continued to build its state in a spiritual simulation distributed across members hearts and minds. Purpose-built for the eternal progression of mankind, this virtual reality was a spatial narrative framed by the borders of the myth of the separate spheres.

This narrative mapped neatly onto my real world, a reality shaped by the 1990s economic boom and suburban cul-de-sacs. This should have made it apparent that my virtual world and what I’d considered the real world were both heaven-building simulations built on top of the same engine: American Industrial capitalism, a framework that is astonishingly good at platform extraction. Instead, the reinforcement made both my virtual world and my real world feel inevitable.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929, Herbert Hoover refused to allow federal intervention because he was certain the white American Home(™) would produce a better outcome. He asked companies to maintain steady wages for men. A Wife Guy to the core, he thought mothers were saints who could raise “healthy children” to make American great again.

And yes, pretty much any time “healthy children” were referenced in the early 20th century by a white guy, he was talking about eugenics. Hoover had been talking about “healthy children” for a long time. He was one of the notable attendees of The Second International Congress of Eugenics in 1921.

A White woman with shelves full of food for her family and body bags for her neighbors is a pretty literal representation of how White women have historically hoarded care resources.

Pocket Observatory is not-for-profit project offered to you for free through a Creative Commons license. The continuation of this work depends on support from people like you.