War of the Worlds

A world built with an algorithm is a world without discovery.

My kids went back to school last week for the first time in a little over a month. They were home for 33 days. Two weeks of winter break and then two weeks of Covid. I don’t know what we would have done if mine or Riley’s job involved shift work or time in an office. I know many of you have been in that impossible position during the pandemic. I am so sorry. I am a freelance writer and Riley works remotely, so we made it work.

Kind of.

I didn’t get much professional work done. Our month together, in sickness and in health, left me behind on two time sensitive projects. I published a little less on my newsletter and so the tips that help pay for childcare were scant. I’ve got a lot of catching up to do. In the past, I’ve found I pay a three day penalty for every one day of disruption. I think that’s because each catch up day holds the potential for compounding disruption. If that formula holds true, it’ll take 99 days to make up for the 33. I’m trying not to think about it. Anyways. January is almost over. And that’s something.

This essay is about world-building, Studio Ghibli, constructs, teen girls, hovering parents, social media, and the upcoming Magnolia update. It’s a whole made of fragments and chaos. (Which will make sense if you read it.) Thanks for being here. I am so grateful.

We only did math once during what I am calling My Kids’ Covid Sabbatical. How many fruit popsicles do three feverish children need to get through an eight-movie Studio Ghibli marathon? (The answer is 17 popsicles.) We watched our favorites: My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, Ponyo, The Secret World of Arrietty, Howl’s Moving Castle, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Castle in the Sky. It was such a relief to slip into those worlds.

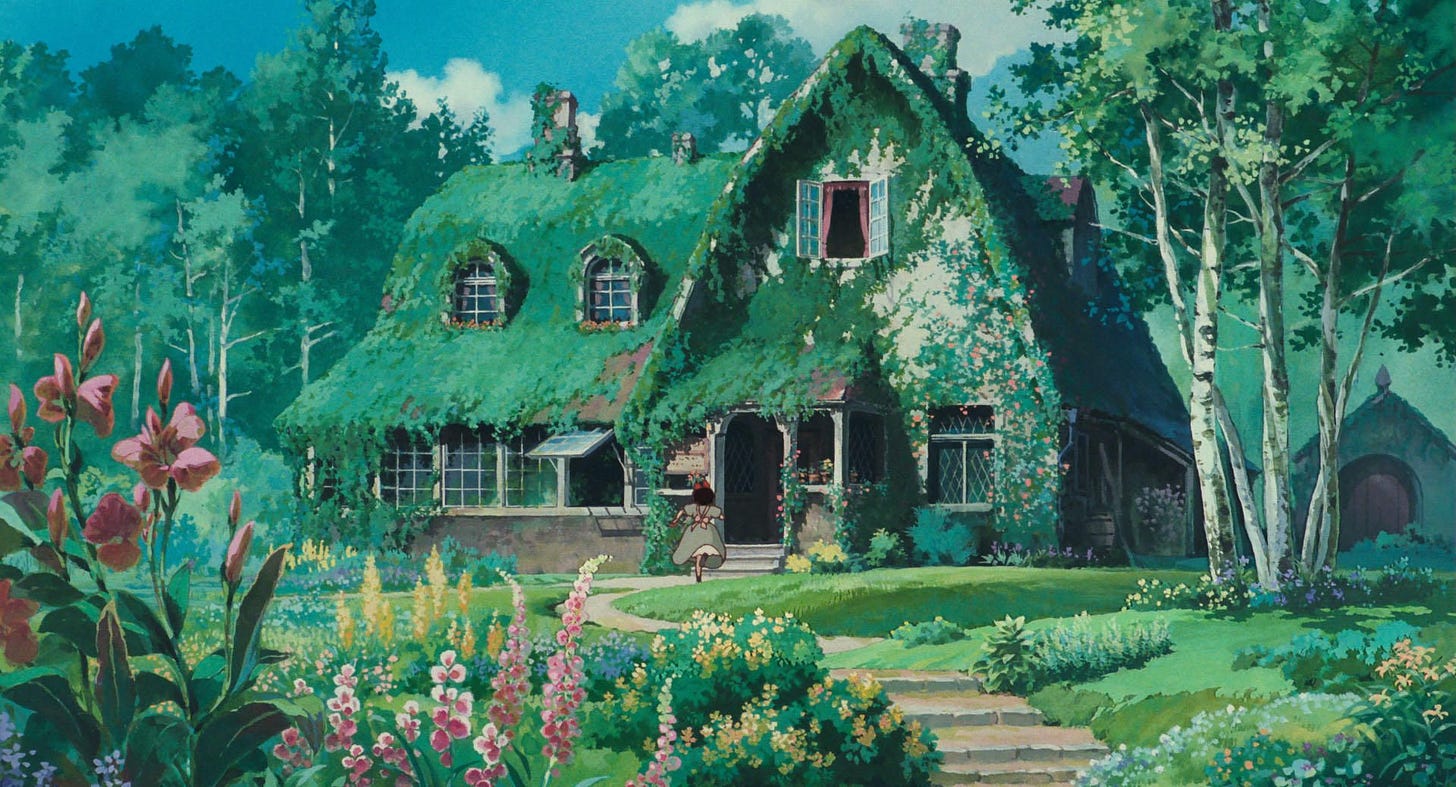

I’ve never encountered another world builder like Studio Ghibli’s co-founder, Hayao Miyazaki. World building includes the development of culture, currency, flora, fauna, laws, geography, history and belief. So many worlds are built for a single end, a plot or a purpose. They always feel false. Miyazaki understands that creation isn’t concerned with ends. He once said, “The creation of a single world comes from a huge number of fragments and chaos.” That’s why Miyazaki’s worlds feel true. They are layered with the seen and unseen, the known and unknown, the sensed and insensible. There’s no end to them, no known beginning either.

Did you know that, while making a film, Hayao Miyazaki writes poems about each of his characters so animators can understand the nuance of each character's personality more deeply? pic.twitter.com/v75sBml80d

— Into The Forest Dark (@ElliottBlackwe3) January 24, 2022

The creation of a single world comes from a huge number of fragments and chaos.

Sometimes those fragments are whole worlds peaking through time and foliage. Like statues and shrines that sit beside roads, before tunnels and beneath trees. The carved stone and wood is evidence of unseen things. The world of spirits, yes. Statues and shrines are one way people make unseen things like spirits seen. But they are also proof of the world of the people who were moved to carve them, the people who moved past them, the people who stopped before them. Their physical condition offers proof of the years that passed them and the years that marked them. They remind us that all the moments before this one comprise an unseen world composed of fragments and chaos. And that moments after this one do the same.

Sometimes the characters in Miyazakis’ movies past a shrine, a spirit, a tree, a moment without recognizing them. They move through a world formed by worlds they’ll never see. A loss. The stories are moved forward by the characters who stop and see. Discovery in Miyazaki films isn’t about collection, it’s about recognition. And once a character has learned to recognize one unseen world, they are able to recognize another. Sometimes, this recognition helps them navigate chaos. Other times, the discovery is enough. In many of Miyazaki's films, it’s a girl doing the discovering.

The female leads in Miyazaki’s films are as layered and unknowable as the worlds they move within. Boisterous, thoughtful, sure, uncertain, right, wrong, hopeful, disappointed, jealous, generous, persistent. Each girl is a world made of a huge number of fragments and chaos. My girls love them. They see themselves in them. I do too. Margaret is Kiki. Viola is Mei. Brontë is Ponyo. Miyazaki's movies are hand drawn. There’s no 3D rendering. But each girl is so whole. The pieces of Kiki, Mei and Ponyo that aren’t drawn into any one frame - the back of a head, hem of a skirt, palm of a hand - must exist outside of it. The best depictions of girls live beyond their framing.

Miyazaki’s worlds don’t exist to serve girls, but they haven’t been built to be served by them either. I can’t say the same about the world my girls move through. Like Miyazaki’s worlds, our world is made of fragments and chaos. Humans use constructs to try to sort through the pieces. We tend to seek order instead of understanding wholeness. Many of those sorting constructs are exclusionary, violent or diminishing. And many of them are aimed at girls.

Schoolgirl pastoral is a genre of fiction, not a memory of the past.

During my adolescence, I felt too earnest, too thought-crossed, too thick-thighed and too wandering to fit into the frame of late 90s/early 2000s girlhood. I thought I was just a girl moving through the wrong world. How could I exist in the age of the ultra-low rise jean and unbothered teen? If only I’d been born earlier when everyone wore dresses and talked over tea. I was sure that world was built for me. I think many of us fall victim to some version of this fallacy. Sometimes we pretend the world was once a better, simpler, freer place to be a girl. But schoolgirl pastoral is a genre of fiction, not a memory of the past.

This world has always been a hard place to be a girl. But some people have built a worse world for some girls than others. White supremacy is a construct with ordered violence extending to many people in many places. In America, white supremacy excludes Black girls from the world of girlhood. A. Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez wrote about this in their New York Times piece, Why Won’t Society Let Black Girls Be Children. As a child they “experienced what academics call ‘adultification,’ in which teachers, law enforcement officials and even parents view black girls as less innocent and more adult-like than their white peers. This perspective often categorizes black girls as disruptive and malicious for age-appropriate behaviors.”

While few are interested in protecting girls, many are eager to define girl. Every definition is a sorting construct.

While few are interested in protecting girls, many are eager to define girl. Every definition is a sorting construct. Sometimes those constructs are enforced by the law. Last year, Florida’s House of Representatives passed a bill that required student athletes to undergo a pelvic exam if their girlhood was disputed. The bill was revised last summer to specify the exam was, “an examination of the organs of the female internal reproductive system using the health care provider’s gloved hand or instrumentation.” In our world, the penalties for living beyond girlhood’s constructed definition often include violation.

I know people build harm into this world. But I used to think complete world building only happened in things I could walk away from - books, movies, theme parks. I was wrong. I carry worlds with me every day. They're apps on my phone. Social media platforms are world building projects. Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat. Each exists as its own whole reality with engineered customs, laws, currencies and digital geography. We often slip into these worlds seeking relief from the world we live in. Our daughters slip into them too.

In 2018, Pew reported that YouTube had “become the most popular social media platform with 85 percent of 13 to 17 year olds using it, 72% use Instagram, 69% use Snapchat, 51% use Facebook, and it’s estimated that 69% of US teens are monthly TikTok users.” When they release a new report, it's probable that every number will have gone up. The pandemic revealed so many things worth escaping. We claim to know the risks of these platforms. But I wonder if we’re able to truly see them.

Facebook’s internal research showed Instagram led teen girls to have higher incidences of suicidal ideation and plummeting self-esteem. TikTok is run with an algorithm coded with racist, fatphobic bias. Youtube spreads radicalizing misinformation. Snapchat has become one of the easiest places for teens to buy drugs, many of which are laced with lethal substances. The platform promised to crack down as investigations revealed teen overdose deaths associated with app enabled purchases. And then there are the dangers of over-exposure and virality.

In an algorithmic world, past moments are data and future moments are sequenced. Nothing is unseen and nothing is chosen.

These apps flatten girls until they can’t see any part of themselves unless it’s in frame. Like any false world, these worlds can be wholly known by anyone with the right key or code. They are designed for a single end - to extract data from their users. Apps are worlds built by algorithms. An algorithm is a sequence of well-defined instructions used for automated decision-making. In an algorithmic world, past moments are data and future moments are sequenced. Nothing is unseen and nothing is chosen. A world built with an algorithm is a world without discovery.

A world built with an algorithm is a world without discovery.

When people find out our kids aren’t allowed to have social media or web browsers on their devices, they think we're helicopter parents. But the reality feels more like letting them fly away. Social media allows a parent to follow their kids and their friends. Sometimes literally. But even if a parent gets kid-blocked, the algorithm can help them follow their child to the places they’re being pushed. Algorithms manufacture trends and trends manufacture behavior. That’s not always good, but it is knowable. Keeping our kids off social media make them less knowable to us. Maybe there’s no discovery in an algorithmic world, but there’s also no surprise. Sometimes surprise hurts.

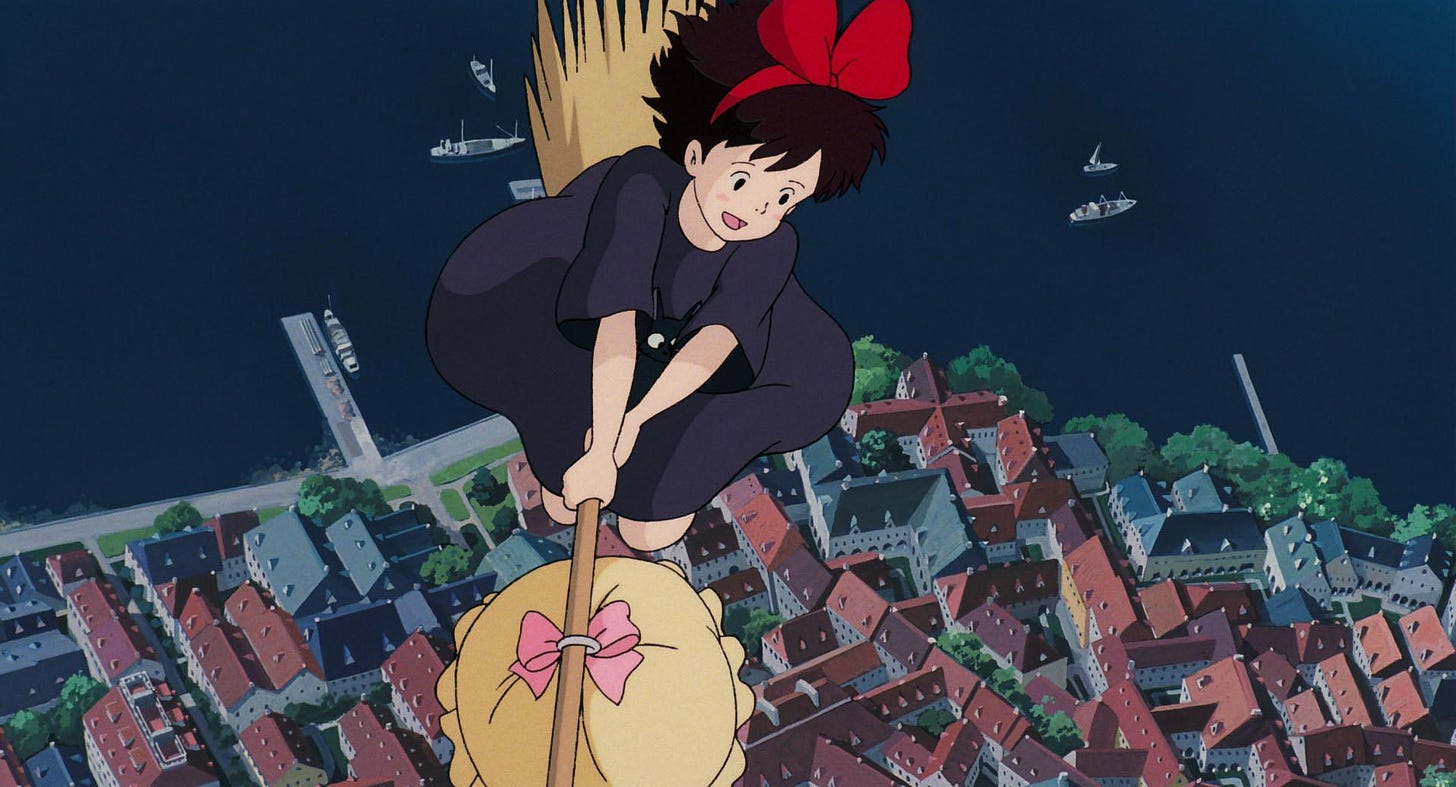

One of my favorite Studio Ghibli movies opens with a surprised mother. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, Kiki is a 13 year old witch. In her world, witches leave home at 13 for witch training in a new city. While in the city, a witch needs to discover her special power. This isn’t Harry Potter and Hogwarts. There’s no admission letter or school. She doesn’t meet other witches on a platform before setting out. She’ll fly away from home alone. Kiki gets to decide what night during her 13th year she’ll leave. When the movie starts, she’s chosen next month’s full moon as the night she’ll say goodbye.

The viewer isn't told why this type of training exists. We don’t know who organizes or enforces it. There’s no lore or expanded universe. It’s not really our role to comprehend the world. We’re supposed to witness Kiki’s dawning comprehension of herself within it. (Sometimes it feels like that practice of witness is the biggest part of my job as a parent too.) We attend as Kiki makes a discovery within the first moments of the film.

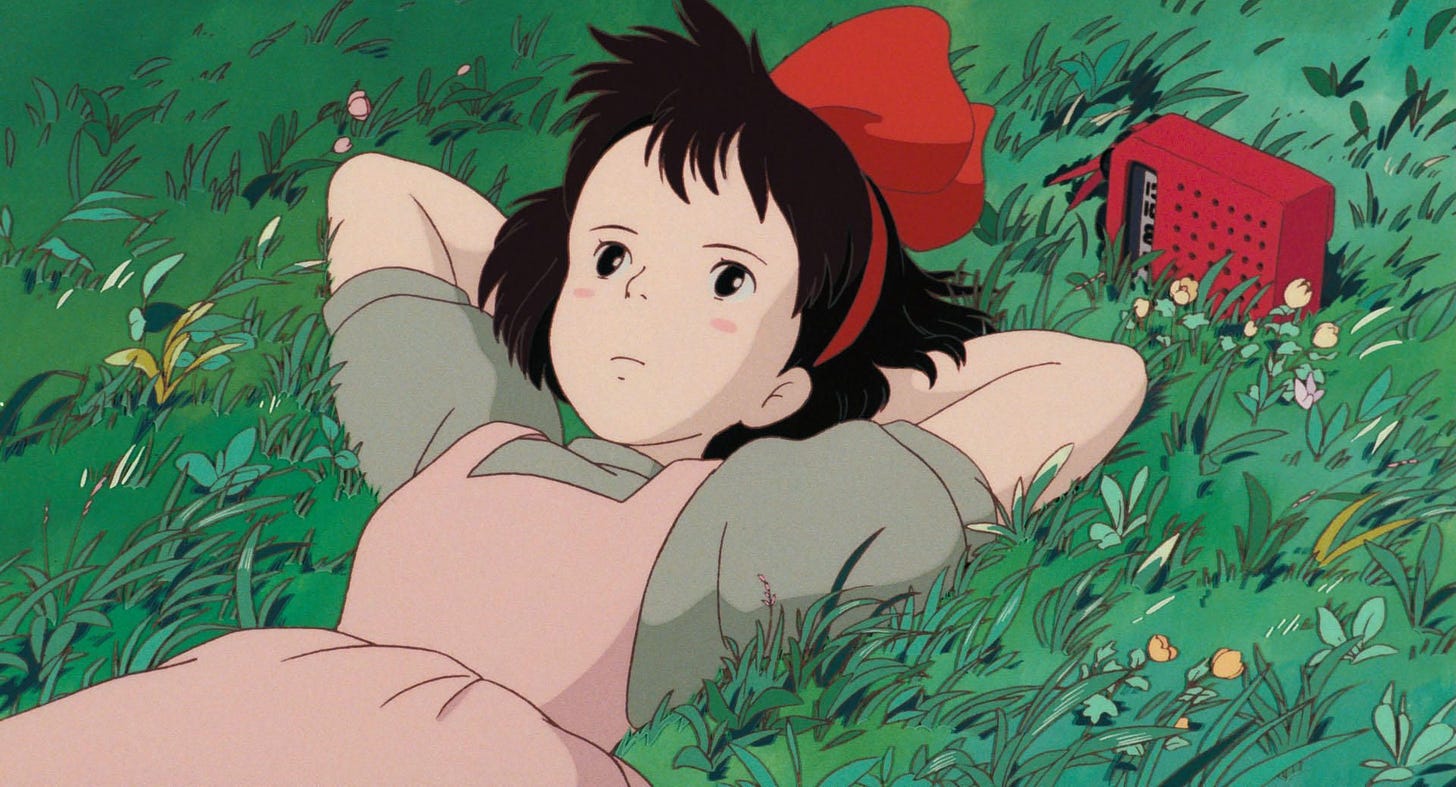

She’s settled on a little hill, a breeze moves the wildflowers on the hill and the red bow in her hair. The movement helps us see Kiki’s stillness, the kind of stillness that lets you see unseen things. A little radio plays next to her, but she seems more focused on the sky than the sound. The sound helps us hear Kiki’s quietness, the kind of quiet that helps you hear unspoken things. Scenes like this are common in Miyazaki’s films for a reason. Zito Madu wrote movingly about the care Miyazaki extends to Kiki in this moment,

“Before the action begins, Kiki gets to rest. She is given a chance to take a metaphorical deep breath and simply be. In an interview with Roger Ebert, Miyazaki called those scenes instances of ‘ma' an old Japanese word loosely translating to emptiness."

The announcer on the radio says it’s going to be a clear night with a full moon. Kiki’s eyes widen. She’s discovered something. She gets up and runs home. Kiki’s mom is making a potion when Kiki bursts in to share her discovery. Tonight is the night, it’s time for her to leave for witch training. Her mother is surprised. Her potion boils over while Kiki runs to tell her dad. He’s packing the car for a weekend father/daughter camping trip. The trip won’t happen now. Neither of her parents are ready for her to fly where they can’t follow. But they recognize Kiki’s discovery. She's discovered that the time to begin is now.

Once Kiki takes flight, there’s no sequence of instructions driving Kiki to a certain end point. She doesn’t even know where she’s going. She’ll fly on her broom until she sees a city and has a a feeling of recognition. Then she’ll stop. Her witch training has no curriculum, there are no standardized metrics. There is only one requirement. Kiki must choose to train in a city with no other witches. A practical consideration, perhaps, as it spreads witches out across the landscape. But it also gives Kiki access to solitude. Solitude is the state of contemplation we rob ourselves of as we scroll through our phones. Ma is a kind of solitude.

There is only one measure of fulfillment. Kiki will know her training has been successful when she’s discovered her power and learned to apply it to help herself and others. The first time I watched the movie, I thought she’d discover some grand gift just in time to save the world. That’s how these stories go, right? A regular girl discovers that she is actually exceptional. Isn’t that what so many of us are trying to discover about ourselves in the worlds of TikTok, Twitter and Instagram?

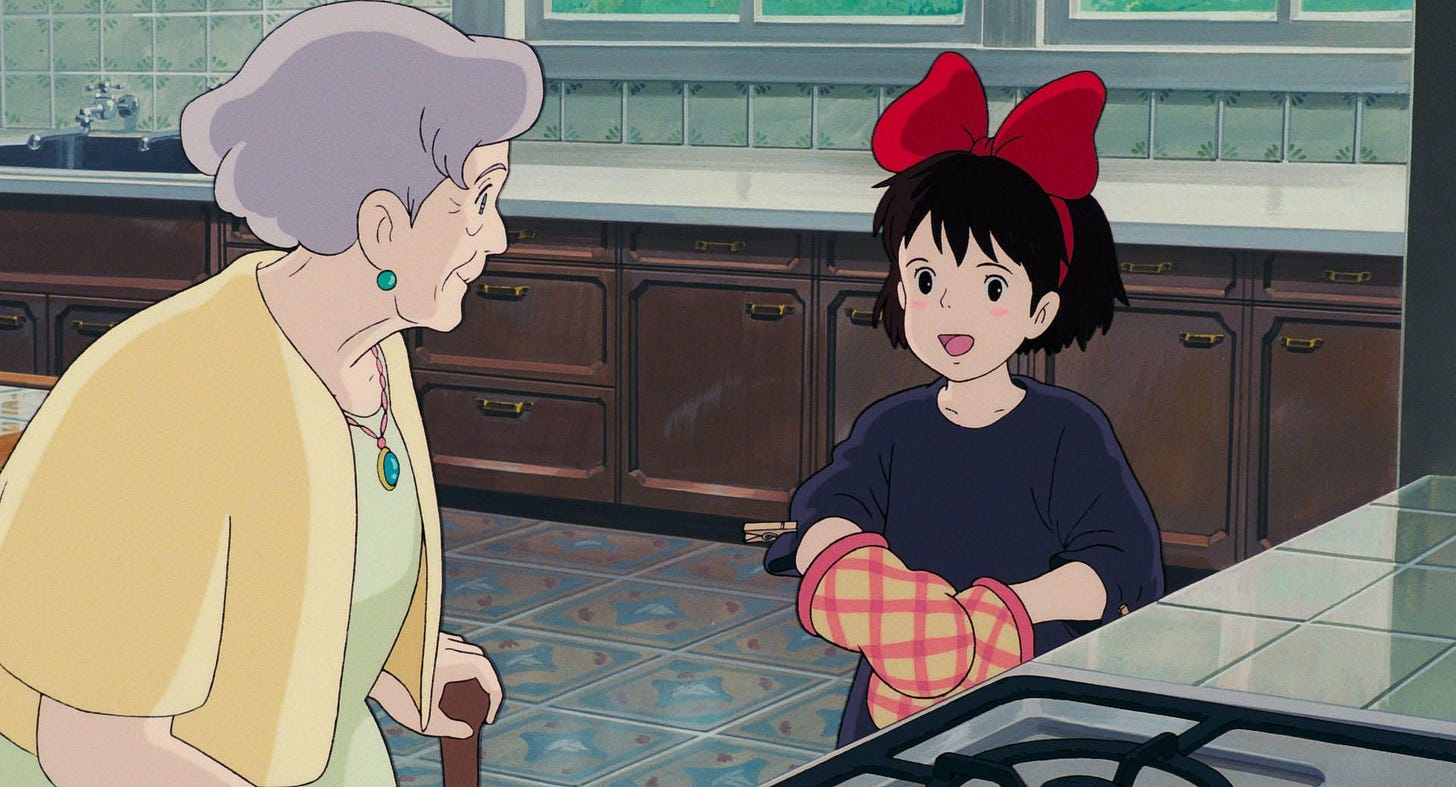

Kiki doesn’t discover a world saving power. Instead, Kiki learns she is a regular witch who is very good at a regular witch thing. Kiki is good at flying on a broom. She uses this skill to start a delivery service. Kiki connects the city’s inhabitants with her deliveries: gifts, bread, a herring and pumpkin pie made by a grandmother for her granddaughter's birthday.

Some of the the deliveries go awry. One because of Kiki’s carelessness. A toy is dropped from her broom down into the woods. Another because of the recipient’s thoughtlessness. The granddaughter doesn’t like her grandmother’s herring and pumpkin pie. When something goes wrong, Kiki discovers other powers, like her desire to make things right. And other skills, like her ability to connect with people. She learns to ask for help and she learns to offer it too.

Kiki makes mistakes, hurts feelings, gets jealous, and loses her sense of self. Transitioning from early childhood to the spaces that exist beyond is painful, even for a girl witch. Kiki loses her power to fly as the self-doubt that often seeds that transition blossoms. No one can build a world without pain, not even Miyazaki. Instead, he built a world where Kiki is free to discover. And her discoveries - seen and unseen, from within and without - help her navigate the painful transition. Eventually, she can fly again.

At the end of the movie, Kiki uses her power to save people stuck in a runaway dirigible. Thousands watch from below as Kiki saves from above. But Kiki and the viewer know this exceptional moment is really and truly an exception. That one grand flight witnessed by a crowd will be followed by thousands of connecting flights witnessed by the clouds. The movie doesn’t end with Kiki saving the people in the dirigible. It ends with her running her delivery service in a community she’s learned to know. It ends with her doing the things she’s discovered she can do.

Kiki’s world had to be built because it doesn’t exist. But, absent talking cats and flying brooms, it could. We could build a world where girls have the resources - time, support, solitude, liberation - to discover. How would we code our technology and our treatment of those who claim girlhood in that world? In what ways would we let them be?

By keeping our daughters out of social media worlds, I know we've severed a type of connection. It’s harder for them to make friends when many of their peers communicate over Snapchat about TikTok. In giving them a chance to experience solitude, we've caused some isolation. I understand why parents let their kids enter those worlds. I don't think those parents are wrong. And I never feel completely right about our decision. People can often find community on social media when they are denied community in other spaces. People like me.

I know that social media can connect. Stay-at-home motherhood left me isolated. I found community and communion on Instagram and Twitter. Those spaces also gave me my writing career. A stay-at-home mom with a high school degree needs a platform to be, well, discovered. Some of my closest friendships were formed through social media. I have lifelong friends I've never met in real life. And so for years, I’ve justified my own building in those worlds because of what I’ve gained from them.

But my recent piece about home makeovers, Magnolia Network and influencer capitalism forced more contemplation. Instagram and Twitter have sustained me, but they’re worlds built on and for extraction. What can a world built to take truly give? If I don’t want my daughters in those worlds, should I stay in them? And if I stay - for work, community, or anything else - what can that look like?

Later this week, I’m publishing an update on the Magnolia story. A lot has happened since the first piece went up. I’ll interrogate what is known publicly and what I learned privately, about that whole thing but also about myself. In the weeks since that essay was published, I sought solitude. I was quiet until I heard, still until I was moved. I discovered I have to make some changes. I want to be a better world-builder. And I hope to have you join me. (Hope is a kind of unseen world too.)

Until that update, I want to share the final paragraph of Zito Madu’s excellent essay about Kiki’s Delivery Service,

“Kiki, in keeping with Miyazaki’s affection for his characters, is treated as humanly as possible. During her adventure, she’s given moments of relief, gaps of peace where she doesn’t need to do anything but exist. These gaps are wonderful signals that life is much more than plot and constant action. They demonstrate that within the grand adventure between birth and death, one should also sometimes sit in the grass on a lovely sunny day and revel in the joy of being.”