The Sounds of War

The fighter jets that invaded Iraq train over my backyard.

This is the first installment in a series examining the rights of the home in a world of warring states.

I live in a neighborhood that looks like a movie set. Big arching trees and wide sweeping porches. There’s a little bookstore and a coffee shop with scooped ice cream. My neighborhood doesn’t just look like a movie, it sounds like one too. If someone mixed a soundscape for a pleasant neighborhood, it would sound like mine.

On winter mornings, shovels scrape against the sidewalk clearing snow. I can hear them scratch through my bedroom window. In the summer afternoons, kids run through sprinklers in their backyards. I can hear them squealing from my front porch. We’re near one of the city’s hospitals, so here and there a siren in the distance. Sometimes sea lion's barks bounce from the Denver Zoo across Colorado Avenue.

There are other sounds that belong in a neighborhood. Hellos shouted from a slowly passing car. The mailman running up front steps. Music playing in a kitchen escapes through a cracked window into the air around me. Sometimes a child cries somewhere, but it’s the kind of cry that a parent will fix with a hug.

There is one sound too jarring for a pleasant neighborhood soundscape

There is one sound too jarring for a pleasant neighborhood soundscape. The recurring sound of US fighter jets flying over our house. I was in my backyard with my three year old the last time it happened. All sound is vibration but the sound of a jet is so forceful, you can feel the vibration. The sound waves vibrated across and through my body. My daughter held her hands up to her ears and cried, “No! Stop!”

Jet noise, one of the loudest sounds manufactured by humankind, comes from turbulence. Most of us only know about turbulence from hitting pockets of the stuff on flights. But turbulence doesn’t only exist in the air and it isn’t all bad. Turbulence is just “the complex, chaotic motion of a fluid”. In physics, a fluid is anything that flows. Liquids are, of course, fluids. But gasses and granular materials like sand are fluids too. Life needs turbulence. Turbulence in our atmosphere mixes warmth, wetness, CO2 and pollutants. It keeps our biosphere balanced.

Life needs turbulence.

Turbulence looks completely disordered, but it’s not. There are patterns produced in a turbulent wake. And while turbulence isn’t always bad, it is a problem for us. Because while turbulence has order, we can’t predict it. We do not know when or why a smooth flow of fluid will become turbulent. And once it does, we do not know how to predict what that complex, chaotic motion will look like. We’ve got no comprehensive understanding of how to stop turbulence once it begins. Turbulence is one of the oldest mysteries of physics. There’s plenty of natural turbulence beyond our ken or control. The naturally occurring, unpredictably ordered chaos should be enough. But it's not. We manufacture turbulence with things like fighter jets.

When a jet flies, it eats up the sky. A jet engine uses a fan to suck in huge amounts of air. It then compresses that air to make it flammable. The ready to burn air is pulled into a combustion chamber where fuel is injected. After injection, a spark turns the mixture into burning gas which escapes out of the other end of the engine. This forceful exit pushes the engine, and the jet built around it, forward. Before the air is eaten up by the engine it is a relatively cool, low-velocity flow of molecules. The air expelled from the engine is a hot, high-velocity flow of molecules. When the high velocity air that’s passed through the engine hits the low velocity air around it, the result is a fierce turbulence.

There is nothing but air between my home and the machinery of war.

That turbulence creates sound waves powerful enough to move down the sky for miles until they hit me and my home. The wave crests against my cells while my daughter covers her ears. Those sound waves feel like an invasion. When the waves aren't vibrating, I can pretend that there is restricted airspace somewhere between my home and that jet. A barrier that protects my home from the force of the state and from the force of the state’s fights. But in the backyard with my baby, those turbulent vibrations shake me unimpeded. There is nothing but air between my home and the machinery of war.

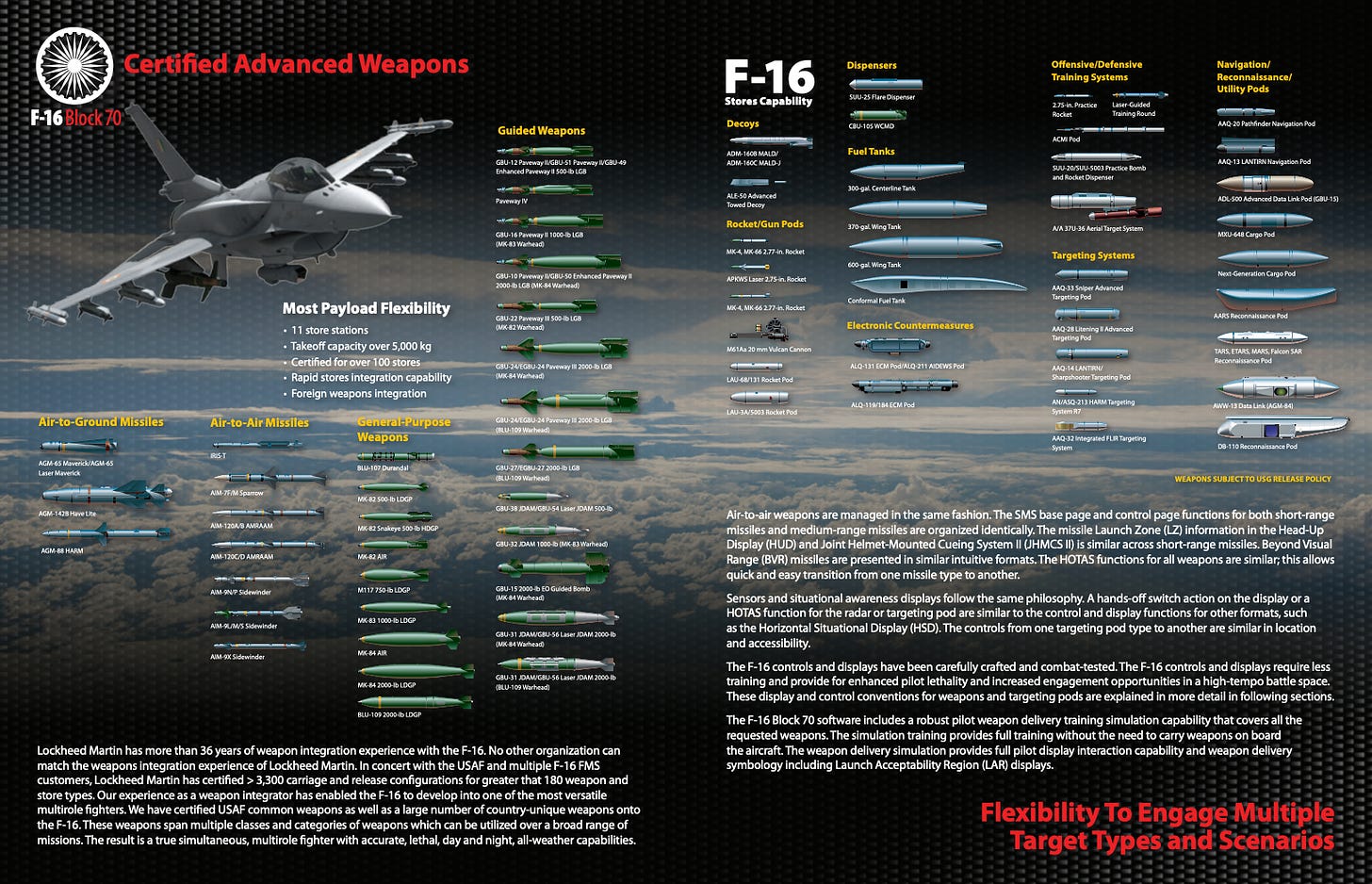

The jets that fly over my home are F-16 Fighting Falcons. The F-16 is known for a few things. It’s got a bubble canopy that provides increased visibility for pilots. When a pilot flies over us, do they look down while we look up? The seat in an F-16 is reclined so that pilots are protected from the effect of g-forces. The human body wasn’t built to move through the air as quickly as a fighter jet. Apparently, the jet is fairly easy to maneuver.

That maneuverability comes in handy when using the M61 Vulcan Cannon built into each F-16. This cannon fires bullets not balls. Up to 6,000 rounds per minute. It is mostly used for close range fighting in the air or for strafing. What is strafing? I am so glad you asked. Strafing is the term for when a low flying aircraft fires at something or someone on the ground. It is always, of course, less risky to kill from a distance. Every F-16 has 11 different locations fit for “air to ground missiles, rockets or bombs”.

I came of age alongside counterterrorism.

My friendly neighborhood F-16s belong to the 120th Fighter Squadron. This squadron traces its origins back to WWI. Its current mission is to protect “midwest America” while also flying counterterrorism missions. I came of age alongside counterterrorism. On March 21, 2003, weeks after my 18th birthday, I watched my country bomb Baghdad in a televised primetime counterterrorism event.

It was the carefully composed opening scene of the Iraq War.

Commentators called it Shock and Awe and narrated it. It was the carefully composed opening scene of the Iraq War. Perched on my living room couch, knees drawn up to my chin, I watched a real city explode, one air to ground missile at a time. Bewildered, I switched from network news to cable news. A little animated American flag waved in the upper corner of the screen when I stopped at Fox. I switched from cable news to network news. The flag was gone, but the scene was the same.

I was young and unquestioningly patriotic. But I was also worried. What I saw happening on the screen looked a little like a fireworks show. But wasn’t it really violent? Weren’t people dying in their homes while I watched? The news commentators across networks assured viewers that casualties would be low. These were “surgical strikes” designed to protect civilians while leveling terrorism. This was a fight between states but the homes in those states, and the people sleeping in them, should be protected. A home cannot help where it is.

I didn't know unnecessary death is a principle of the doctrine of war.

A war fought without civilian death seemed like the only kind of war to fight in the modern era. It all seemed so logical. And because it seemed logical, it seemed possible. I didn't know unnecessary death is a principle of the doctrine of war. Or that homes are rarely safe from principles.

That March primetime invasion was the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom. By May, over 7,400 Iraqi civilians had been killed. In the first two years of the Iraq war, a reported 24,865 civilians were killed. The US-led forces didn’t directly kill all those people. They were directly responsible for about 37% percent of civilian deaths in those first years.

Children were “disproportionately affected” by airstrikes.

Civilians killed by American forces were mostly killed by explosives. Airstrikes caused a majority of the explosives deaths. Children were “disproportionately affected” by airstrikes. Little legs have a hard time running away from swiftly dropping bombs. Nearly 5,000 of the civilian deaths during the first two years of the war were women and children.

They were killed by the turbulence left in the wake of the engine of war.

A majority of post-invasion deaths were not the direct result of an American finger putting pressure on a button in a cockpit or a trigger on a gun. They were killed by the turbulence left in the wake of the engine of war. 17,000 civilians died because of anti-occupation violence and post-invasion criminal violence.

I feel a pressure wave of children who heard that same jet and whose hands went still.

How many Iraqi children died while I watched coverage of those first few days of the war? We could not hear them over the racket of planes, bombs and grimly determined commentators. The 120th Fighter Squadron was in Iraq for the opening moments of the invasion. Sometimes, when one of those F-16s flies over my house, and my daughter holds her hands to her ears? I feel a pressure wave of children who heard that same jet and whose hands went still.

Most, if not all, of those children had homes where they were safe and loved. When a child has a safe home, it is what they ask for when they are afraid, sad or uncomfortable. Whispered in the corner of a sleeping bag at a sleepover that’s got too little sleep. Wept in a stall in the bathroom at school when someone has been unkind. Whined in the back of the car after a long drive,

“I want to go home.”

A home in a state under attack is a home under attack.

But a home isn’t safe in war because a home has no rights in a war. We’ve decided a home derives its rights and protections from the state it resides within. A home in a state under attack is a home under attack. And then, an uncomfortable whisper. If we cannot untether the home from the state is a home in a state that attacks a home that attacks?

After 150,000 Iraqi deaths, no evidence of weapons of mass destruction and too many American men and women lost, our fighter jets left Iraq. The marks of their airstrikes remain.

The 120th Squadron is stationed at Buckley Air Force Base. The base is a 26 minute drive from my house. But it's much closer if you’re flying in a plane that can break the sound barrier. Buckley AFB has been expanding since World War II. Each new war and operation merited more land, more barracks, more weapons. As the War against Terror ramped up in the 2000s, the base added family housing. A reminder that people make their homes where they are.

Buckley doesn’t just expand as we fight wars, it grows in anticipation of wars we still don’t know how to fight. It’s now a Space Force base for the newly established Space Force. It may soon be renamed. I suppose Buckley feels a bit terrestrial. As a Space Force base, Buckley is responsible for providing “combatant commanders with warrior airmen”. Space Force "warrior airmen" are called Guardians and their doctrine is Spacepower, the new form of military power. (Yes, they named it Spacepower. I don't know.)

We are building interstellar infrastructure for the wars we want our children and their children to fight.

We don’t know how to fight a war in space yet. There will be little need for a close range cannon in orbit. And killing at a distance is a bit more complicated when the distance is potentially infinite. Still, a short drive from my home, we are building interstellar infrastructure for the wars we want our children and their children to fight.

Fighter jets continue to fly across our skies while we develop war in space. I am not the only one concerned about the sounds of war. I live in Denver. Buckley AFB is one city over, in Aurora. Buckley's website has a page dedicated to Jet Noise and its impact on the surrounding community. Mostly, the page is five paragraphs of "Yeah. We know. Jets are loud."

On the page, Buckley also expresses concern over the “encroachment” of community development. The base pours an estimated $1 billion a year into the local economy so its concern cannot really be ignored. While acknowledging that it is not allowed to have a say in local issues, the base does seek to sway. “We strive to identify development proposals that may be incompatible with our military training mission.” There is some awareness. Homes are mostly incompatible with military missions. The final lines of the page are unsettling.

The bottom line is we strive to keep Aurora a hospitable place for all of its residents to live and work, while simultaneously accomplishing our training and support to our nation. Of course, we cannot eliminate the impact on the community completely when it is nestled next to an active flying military base, but we constantly strive to be the best neighbors we can be.

In this narrative, the military base is the immovable volcano and a community has been unwisely built against it. If the base erupts in violence or sound, the homes will be enveloped as a natural, inevitable consequence. Why aren't the homes the immovable landforms and the military base an encroaching complication?

I’m not naive.

Melt down the jets' cannons and hang swings from their wing tips.

We could take the engines out of every fighter jet and convert them into generators. Once the tin planes had no hearts, we could fill their cockpits with soil and plant hot house tomatoes. Melt down the jets' cannons and hang swings from their wing tips. We could do all those things and feel more moral and be less safe. Because not every state would let tomato vines curl over their fighter jets' center pedestal displays.

I know that U.S. jets don’t just fly to attack, sometimes they fly to defend.

I know that U.S. jets don’t just fly to attack, sometimes they fly to defend. My grandpa kept fighter planes fighting in WWII. He fixed planes so they could return to the sky and when they returned to the sky, they were used to kill people. It was ugly and complicated and...a war we needed to win. I am grateful to him. And sorry for him too. It's a burden to fight.

It’s the kind of neighborhood a prosperous state promises but rarely delivers.

I know my neighborhood, or the idea of my neighborhood, is one of the things those F-16s were built to defend. It’s the kind of neighborhood a prosperous state promises but rarely delivers. The trash is always picked up and the electricity rarely flickers. And we’ve all decided that living today on land stolen by the state from Indigenous Peoples yesterday guarantees rights protected by and from that same stealing state. And when we do let ourselves see that the state has only ever recognized the rights of the homes of those in favor? We might shift a little to try to get comfortable again. Surely, those jets will always fly over our homes and never fly to them...right?

And here is where I get lost again. A world in which a home’s rights depend on a state’s willingness, or ability, to protect them is a world where no one is really home.

Over 2,300 flights take off from Buckley Air Force Base each year. The pilots train for combat, sucking in the sky and pushing it back out again. But it’s not all training. There’s a page on the Buckley website, "How do I schedule a flyover for my event?" The copy is quick to caution the over enthusiastic reader. So many requests come in each year, they can’t all be accommodated. I've cheered as fighter jets flew over parades. But, if you think about it, that's odd, isn't it? Why do we cheer? When a jet that’s bombed cities flies over a halting stream of high school marching bands and papier-mâché floats?

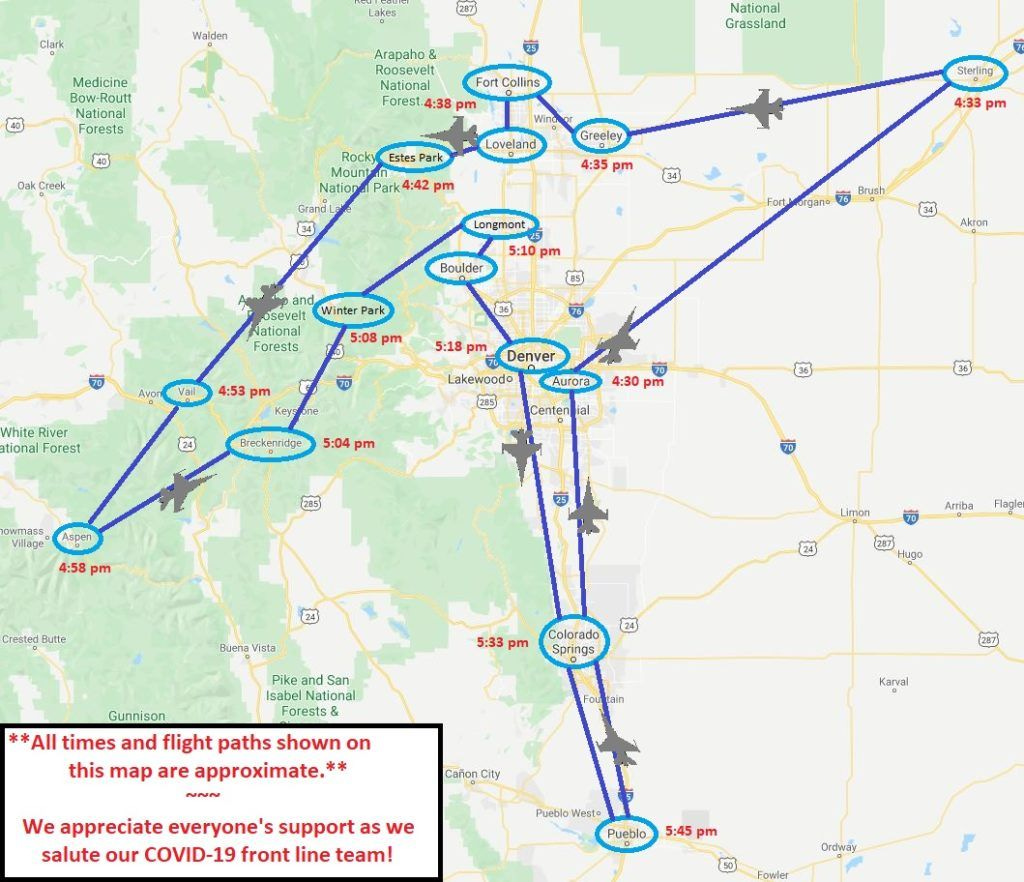

In May of 2020 the US Air force launched Operation American Resolve, a series of F-16 flyovers meant to lift a public demoralized by the pandemic. The first Stay-at-Home Order in the US was given in Puerto Rico on March 15 2020. Between March and May there were 122,300 more deaths than were expected for that time of year. Most due to Covid, some due to the turbulence created by a fast virus and a slow state.

Before the flyovers, Buckley AFB released a map of the flight path so that people knew where and when to look up for the jets. It’s funny what a difference a map makes. If you took that same flight pattern and drew it over Iraq, the homes in the flight path might be full of people cowering instead of cheering. When the jets flew over our house, my toddler was coloring at the kitchen table. She yelled, “It’s too loud, mommy!” But then the jets were gone and their vibrations were too. She shrugged a little and then reached for another crayon.

We will kill and be killed in silence.

I don’t know whether flights over my house will become more or less common as Buckley becomes a full-fledged space base. The planes that bombed Baghdad and scare my daughter will be retired. Who can be satisfied with consuming the sky when space waits? I suppose once wars are fought in space, jet noise won’t be a problem. In most of space, there are not enough molecules for sound waves to vibrate and move through. We will kill and be killed in silence.

A war without sound might be the only thing worse than a war with sound.