Sound of Freedom is part of an augmented reality project

that I'm afraid of getting stuck in.

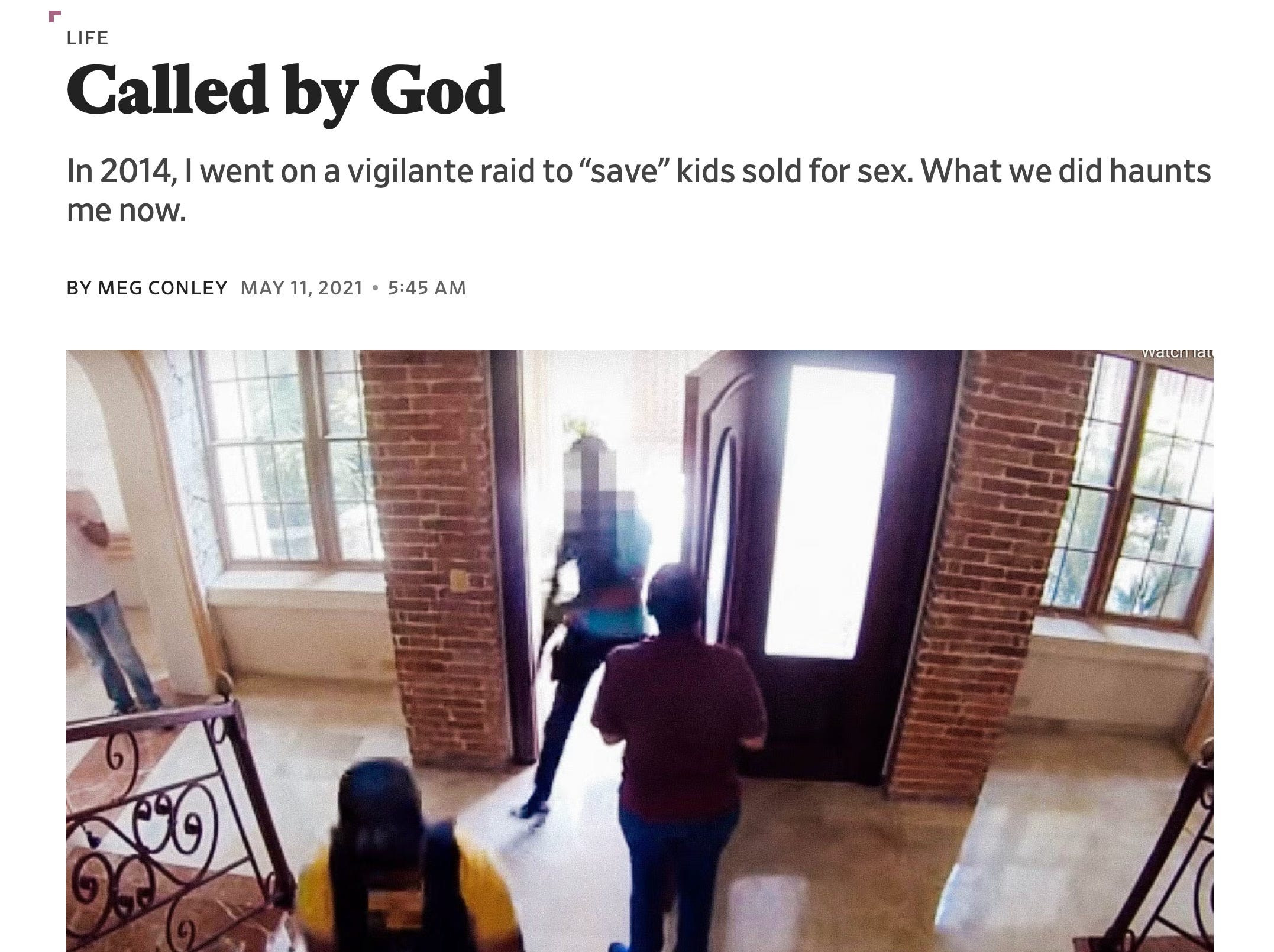

I was recently on Vox’s Today, Explained. They asked me to talk to them about my experience with Operation Underground Railroad, an anti-trafficking organization.

O.U.R. has been in the news because of the movie, Sound of Freedom. In the movie, Jim Caveizel plays a hyped-up version of Tim Ballard, the founder of Operation Underground Railroad.

Sound of Freedom tells Ballard’s story the way he tells it. Ballard frames himself with a low-angle hero shot, even when he’s eating a plate of chicken and rice. I know, because I’ve listened to Ballard talk about himself while eating a plate heaped with chicken and rice.

In 2014, before Trump, before human trafficking was a term woven into our everyday cultural conversation, before I knew I know nothing, I went on a human trafficking raid with O.U.R. in the Dominican Republic. I thought I was saving children.

In 2021, I wrote an article for Slate examining many of the ways I was wrong. I wrote about the raid, its aftermath, and my accumulating horror as I realized how Ballard’s rhetoric helped make the landscape more amenable to Trump, PizzaGate and Qanon. If you’d like to read it before continuing on, this newsletter will wait for you. (Waiting room music plays)

In the years after the raid, I learned O.U.R.s methods aren’t just ineffective, they are dangerous for the trafficking victims subjected to them. I understood that human-trafficking is a real horror that can’t be captured with a Michael Bay filter. I realized Ballard had been willing to put my life at risk so that I could function as the lens getting his hero shot. But there was always a sense that I was still missing the real shape of Ballard’s project. Like I’d correctly identified components of a whole I still couldn’t name.

I can name it now, in terms my fourteen year old would understand.

Operation Underground Railroad is an augmented reality action role-playing game built with the Hero’s Engine. Its leaders have developed a world split into light and darkness, American exceptionalism and entropy, white saviors and demons. Human-trafficking is a real problem with real solutions, but O.U.R. obscures the nature of both the problem and the solutions in service of a white supremacist hero’s journey.

Am I comparing a self-proclaimed human trafficking organization to a video game? I am! What the heck is a Hero’s Engine? Let me explain!

Unlike other types of action video games like platformers and beat ‘em ups, action role-playing games are narrative-driven. They require character development - often in the form of transformation from a regular person to a hero. The fate of a world often depends on the real-time actions of the character.

Video games are ultimately world-building projects. Each game has its own natural laws, rules and structures. A Greek god still rules over the human dead in one game while humans never existed in another. Those worlds are often built using a game engine, a software framework. Engines are a library of features that game developers need from graphics rendering to AI support.

A game engine is basically the underlying technology for a game. The features of the engine affect the types of games that can be built with it. The Godot Engine is free, open source and has become known for its suite of 2D tools. It’s a favorite of indie game developers and people who are more focused on story than immersion.

Unreal Engine is known for its capacity for customization, “density of detail” and real-time dynamic global illumination. (That last bit just means that light in the game works like light in real-life, reacting to the game play and bouncing of objects in real-time, instead of being pre-lit.) It’s a favorite of everyone, but especially people who want to create truly immersive gaming experiences.

Like most world-building projects, video games center a single person or, in the case of multi-player games, a specific group of people. The simulated world exists in service to the goals of the developer and players.

The more real a built-world feels, the more tied a player can feel to it. This is part of the reason tech companies keep trying to make virtual reality happen with VR headsets. If they can augment a customer’s reality with their design, they can influence the real-world, real-time actions of the customer.

People are very worried about the effect VR headsets will have on society if they gain traction as daily wearable tech. And I share their concerns! But I didn’t have to look through a pair of goofy looking glasses for O.U.R. to augment my reality with their designs, I just had to look out a window.

Just a quick cut scene to 2014, when the jump team and I landed in the Dominican Republic:

After we’d gotten through customs, we were greeted by a man who worked for O.U.R. He’d been in the area for weeks, prepping for the raid. I learned later that prep included pretending to be a tourist interested in trafficked children.

On the car ride through Santo Domingo, I looked out at a place I’d never seen. I thought it was beautiful. As we drove, the man pointed out landmarks along the way, the way any good tour guide would. The landmarks looked like ordinary buildings and businesses that make up any cityscape. But this man saw them for what they were. And he was there to help us see them for what they were too - geographic coordinates of a dark world that only people with vision could see.

“Do you see that storage facility? Traffickers rent those and then sell kids in them by the half hour.”

He pointed out the window again and again, turning common spaces into battles between good and evil.

There was the world I could see as a normal stay-at-home mom, where storage units are usually just storage units. And there was the dimension of darkness that only the initiated could see, where every storage unit (or Wayfair package) is the site of unspeakable evil. Ballard was called to carry light into that dimension. He, and other people ordained to the work, could see and liberate in that dimension.

As a woman initiate, I was there to witness them as they carried the light. And when I returned to the world I knew, I’d bring my witness with me. That witness would inspire other men to follow Ballard and other women to witness and support all those men. When a man became a savior in that other dimension, he became a savior of the known world too. Using his knowledge of darkness to make, and keep, the known world lighter.

If this sounds familiar to you, that’s because this is kind of the plot of Star Wars. And that’s not an accident. O.U.R. developed its augmented reality with the same engine George Lucas used to create Star Wars: Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth.

Campbell was a literature professor who was certain he’d found something he called the Monomyth, a myth he said repeated across civilizations all over the world, uniting people across culture and time. You might know it as the Hero’s Journey.

In this journey, an apparently average man in the known world is called to adventure. He might at first refuse the call, but circumstances persuade him to heed it. While he is still in the known world, he is often given some sort of supernatural aid to assist him before he crosses the threshold into an unknown world.

Sometimes this unknown world is an actual other physical world, sometimes it’s supernatural realm, sometimes it’s a dimension of his own reality that others can’t perceive. Whatever form this unknown world takes, it’s the place where this apparently average man is destined to be transformed into a hero.

Once in the unknown world, the average man is met with a series of trials and temptations. There are helpers along the way, - often they need him to save the unknown world. It’s only once he’s gone to the deepest, darkest part of the unknown world, the abyss, that the man is given what he needs to transform into a hero. A bit of knowledge, a flask full of elixir, a piece of treasure.

After his transformation, the hero returns to the known world. When he crosses the threshold back into his world, he is still transformed. He is also carrying knowledge or an object that can save the known world. In saving the unknown and known worlds, he becomes master of them both.

Sarah E Bond and Joel Christensen wrote an excellent piece, The Man Behind the Myth, interrogating Campbell’s concept of an ideal, universal myth,

Campbell’s synthetic, undeniably alluring model presented a hero who reluctantly accepts the call to adventure, using the tribulations of his odyssey to reshape himself into the savior humanity needs before returning home. Campbell claimed his theory, which has gone on to influence everything from Star Wars to Disney’s Aladdin, arose from a universal structure inherent in the global myths of antiquity. The problem is, that’s a lie. Campbell’s theory is as mythological as the stories from which it borrows.

They go on to point out that Campbell cherry-picked myths to make the argument for a monomythic Hero’s Journey, ignoring any that did not fit his narrative structure. There is no ideal myth - no correct version with variations. The myth where Medea does not kill her children is as valid as the one where she does. Myth cannot be universal because each myth is a distinct product of its time and place. There are common traits found in myths! But stories only have the power to become myths because of their time-bound details and differences.

And Campbell’s Myth of the Monomyth is proof of that! It had the power to become a myth because it was richly infused with the gender stereotypes and conservative politics of his time and place. Women are goddesses, temptresses or in distress. Only men become heroes. And the collective can only be saved by the individual. It’s an engine with features favored by those trying to simulate Making America Great Again.

These sins of contextual omission allowed Campbell to weave an attractive narrative that found particular favor with his white midcentury audience. Echoing the “ethical egoism” of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, published only a few years earlier, Campbell sold the public on a vision of the individual hero, unfettered from community or history. He gave a postwar readership a seemingly timeless archetype for America’s unique brand of “rugged individualism.” He also helped to create a niche for the intersection of pop culture and pop psychology, paving the way for less savory exploitations of narrative by people like Jordan Peterson. Peterson has latched onto Campbell’s use of archetypes and gender roles and interprets them as the means for saving humanity from political polarization.

Ballard and O.U.R. latched onto Campbell’s Monomyth and used it to create a narrative that supports Christian nationalism in the guise of saving the children. The organization’s Hero’s Journey seems designed to illustrate that places where white men are less likely to rule are places where children are more likely to be trafficked.

In O.U.R.s narrative, white Christian men are called by God to go into the unknown world. Of course, the “unknown world” in this case is mostly mapped onto countries that have suffered the ravages of imperial colonialism before asserting their right to self-rule. Going from the United States of America to anywhere that white Christian men are not the main demographic counts as crossing the threshold into the unknown world. There is no way to separate racism and white supremacy from this hero’s journey.

“Saving the children” has been used to justify all kinds of Christian nationalist cultural projects, from Manifest Destiny to Moms of Liberty. Of course, it’s relatively easy to pick apart the worlds built by those two projects. God never told Americans to move west to redeem the land. The land didn’t need redemption. But colonists had been pushing to move west as a means of wealth-building since before the Revolutionary War. And anyone with even a bit of sense can see that Moms of Liberty is just a straightforwardly racist organization. It should actually be named Moms of Lynching.

But human-trafficking is a real blight, with complicated causes and systemic solutions. And so it can be difficult for the average person to separate the real world from the one generated by the myth. Which means O.U.R. can generate a new layer of perceived reality and an ignorant person might not even notice the occasional glitch. In 2014 when I went on the raid with O.U.R, I was a very ignorant person.

Campbell’s Hero Engine was later used to render the augmented realities that came to define Trumpism, Qanon and anti vaccine propaganda. But this was all before Trump’s presidency, before Qanon, before the Wayfair Conspiracy, before Instagram became populated with pastel-colored stories calling for other moms to “save the children” from a deep state pedophile ring. So I did not recognize the hallmark of conspiracy theory on O.U.R.s simulated reality. But it did feel familiar. And when new things feel familiar that can make them feel true.

It wasn’t just because of Star Wars. I’d grown up believing the world was split into two dimensions. There was the private sphere, the dimension of women and children. And there was the public sphere, the dimension of men. Men could move between both the private sphere and the public sphere, because they were masters of both.

My childhood religion reinforced the simulation of those spheres, but so has every legislation session that hasn’t passed universal paid maternity/parental leave, universal healthcare and universal childcare. America is truly exceptional in its refusal to acknowledge we all live in the same dimension where we don’t need heroes, we need affordable housing.

Isn’t the traditional nuclear family, with its wife who stays home and its husband who crosses the threshold every morning just the Hero’s Journey played out every day? Without a meaningful social safety net, the only way the American home can survive is if there is a hero returning with saving wages each night.

Shortly after the raid, I got on a call with people from O.U.R. They were discussing the marketing and development plan covering the next three years, 2015 to 2017. O.U.R. was brand new and they needed to recruit donors quickly to keep up with their goals.They brought me in on the call it so I could understand, and help push, the organization’s brand narrative. It was the Hero’s Journey. Even then, O.U.R. understood that their call to action was about heroism, not children.

The person on the call explained how Ballard’s Hero journey would be made clear - he followed a call of adventure (or in his words, the call of God) to leave the CIA. That was a good story, but it wouldn’t really raise much money. There was no call to action, because Ballard was already transformed.

But the potential donors were not heroes yet. They could go on a Hero’s Journey by virtually following O.U.R. jump teams on trafficking raids. Using social media, text messaging and emails, O.U.R. would give sneak peeks into upcoming operations. That was the call the action. People would heed the call by becoming donors. That’s how they crossed the threshold.

Those donors would get special text messages before a raid occurred, asking them to pray for the jump team. This was a kind of intercessory prayer, or prayer by proxy, that put the donor in the abyss with the jump team.

When I went to the first documentary made by O.U.R. about itself, they had “I am an Abolitionist” signs for people to hold in their photo booth. It was supposed to be a way to raise awareness to “save the children.” I posed with one. Which only raises awareness that I was a silly, ignorant, duped woman.

After the raid, O.U.R. would send donors what they called a Victory text. With that text, the donor was transformed into a hero alongside the people on the jump team. Instead of using the term hero, they told donors that they could become an “Abolitionist.”

O.U.R. depended on the intensity of that experience to lead the donor to share on social media, as a way to recruit other future heroes to their own transformation. As soon as one operation finished, the cycle began again. How many times can you go through the hero’s journey before believing everyone but you is a villain?

The strategy worked. As I began to notice glitches in the simulation, I watched social media fill up with with images of people holding O.U.R. fundraisers. Women held bake sale and men performed feats of strength. I saw people proudly displaying the “I am an Abolitionist” badges on their websites. They all felt transformed.

Hero making is lucrative in America.

According to Pro Publica, O.U.R. reported total revenue of $3.45 million, with about $2.2 million in expenses in 2014. By 2020, the last year revenue numbers are available, O.U.R. reported $47.5 million in revenue, with just $13.5 million in expenses. That left a net income of $33.9 million. If they just parked that income a money market account, they’d have made $2 million in interest by 2023. Which is interesting.

I don’t know the revenue for 2022, but I do know that the top eight officers of O.U.R. were all paid more than $253,000 that year. Ballard’s compensation came in at a breathtaking $525,958. That only includes compensation through O.U.R. He probably made more through other ventures made possible by his attachment to the O.U.R. brand.

Hero making is also a way to gain proximity to power. In the years after the raid, the Utah Attorney General decided he wanted to be a hero too. And Trump decided he wanted a hero on his team, Trump’s Advisory Council to End Human Trafficking. Ballard spent a lot of his time pushing the border wall and Qanon-adjacent ideas.

Work on the Sound of Freedom script started in 2015, just as the the three-year Hero’s Journey strategy started at O.U.R. In his review of the movie, Rolling Stone’s Miles Klee called it a “stomach churning experience, fetishizing the torture of its child victims and lingering over lush preludes to the sexual abuse. At times I had the uncomfortable sense that I might be arrested myself just for sitting through it.”

Despite the lush preludes to sexual abuse, or perhaps because of them, the movie has become a surprise hit. It’s made over $150 million since it debuted on July 4th. Helped along by a ticket-selling scheme called “Pay it Forward,” which allows people to buy tickets for strangers. At the end of the movie, the actor who plays Ballard entreats the audience to purchase tickets through the pay it forward program. They’ve been through the Hero’s Journey and now it’s time to invite others to be transformed too.

When I wrote the Slate piece in 2021, my DMs filled up with strangers who had the O.U.R. donation page as their link in bio. They accused me of defending pedophiles. It was upsetting, but it didn’t feel personal. Most of the senders didn’t even bother to figure out how to spell my name.

When Sound of Freedom was released, my DMs filled up again, more strangers with O.U.R. as the link in their bio. But it’s not like 2021. These messages are deeply personal, the senders seem to know who I am. They know I have kids. SouEach seems certain my children and I really belong to that darker dimension.

One of the theories is that my children are being threatened by deep state pedophiles. I am being blackmailed into writing anti-O.U.R. screeds in order to save my children. When I think about people layering this augmented reality across my life, I panic. I do not want my family to be part of anyone’s Hero’s Journey.

After Sound of Freedom’s premiere, it was leaked that Ballard has been pushed out the organization he created. I imagine O.U.R. will try to distance itself from Ballard. But we cannot let it. The organization was made in his image. As for Ballard? I am sure he thinks this is just his moment in the abyss. He’ll emerge, victorious and transformed into the true hero he was destined to become.

“One of the most troubling things about Campbell’s Monomyth is its omission of the truth of Greek heroic myth: heroes hurt people. They threaten families and cities. Herakles goes mad and kills his wife and children (even if Disney’s version of Hercules lived happily ever after with Megara), triggering his famous labors as punishment. Achilles prays for his own people to die to pay for a slight to his honor, and his beloved Patroclus gets caught up in this. Odysseus returns home after losing his entire army only to kill 108 of his people and hang the enslaved women of his household.” - The Man Behind the Myth