Man vs. Machine

Political theater can be automated, but political virtue cannot

Originally published by Arc Digital

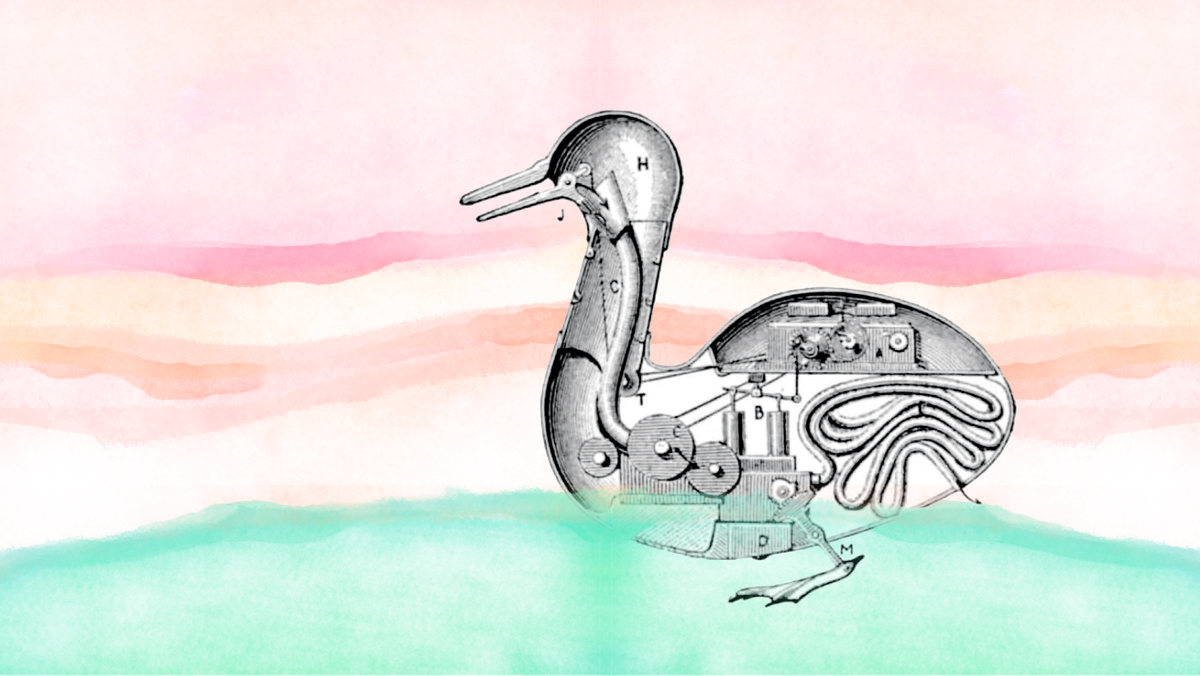

Man loves a mechanism. It is difficult not to love something created to obey. When a machine is well made, it will carry out our will automatically. We’ve been making complex machines since at least the 4th century BCE. Machines to move water, machines to move rock, machines to move needles and thread. Automata are machines that were made to move us.

As old as Greek mythology and created in images as varied as lions, doves, and saints, automata are machines with the purpose of self-propelled, predetermined performance. Ancient and medieval writing is full of people marveling at mechanical bees, at wooden, walking monks and at, in one instance, a weeping Virgin Mary. Mary wept because there were fish swimming in a bowl of water placed inside her head, the movement of their fins splashed water out of her eyes.

Kings and emperors understood the power of automata. In the mid-10th century, Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus supposedly had a ceremonial throne room filled with them. He sat on a throne surrounded by “lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue.” Beside all this stood a tall, golden tree with “branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species.” When a visitor bowed low before the emperor, his throne ascended up into the ceiling with the emperor still in it. When the throne came back down, Constantine VII returned too, dressed in a different robe. The throne and costume change is a particularly Vegas showman kind of touch. I tip my hat across the centuries to Constantine.

We have two historical accounts of Constantine’s gleaming tiki room. The first is from an Italian ambassador, Liudbran of Cremona. The pageantry left him stunned and confused. While he could fathom the mechanism behind the rising throne (a wine press, was his best guess), he admitted that when it came to the roaring, singing menagerie, “I could not imagine how it was done.” The second account is a manual written by the emperor himself for his court, a real how-to guide on the subject of Automata Awe. The automata were to be kept silent and still until an ambassador was formally introduced. And then, “the lions begin to roar, and the birds on the throne and likewise those in the trees begin to sing harmoniously, and the animals on the throne stand upright on their bases.”

As an outsider unfamiliar with the inner workings of the court and machines, Liudbran felt only the mystery and might of the exhibition. Who can blame the poor man for being completely staggered by a tree full of golden, singing birds? However, a Byzantine court insider could easily comprehend the mechanics of the engineered display. Despite their very different perspectives, both outsider and insider understood they were witnessing a demonstration of power.

There are no ceremonial throne rooms in America, but there are plenty of demonstrations of power. We witnessed one when the Senate voted to acquit Donald Trump. Constantine VII would have understood the scene; it was quite an engineered display. It was easy to imagine an aureate tree in the center of the Senate chamber, dozens of Republican senators perched on its outstretched branches, each singing a song of praise, permissiveness, and party line.

Every Republican senator, except Mitt Romney.

When Romney stood on the Senate floor and committed to voting to convict, I felt a sweeping kind of relief. Not because of what the vote meant for the future of Donald Trump, who sits on an ascending throne (only time will tell if there is a robe change when he reaches the top). But because of what the vote can mean for the future of our institutions. Perhaps they, and the people that move within them, can become more than algorithmic mechanisms with preset ends.

Not everyone was relieved by Romney’s vote. Donald Trump Jr. took to Instagram and posted a photo of Romney in high-waisted pants with the caption, “Mom jeans, because you’re a pussy.” Apparently, Trump and Sons only think pussies are good when they are within grabbing distance. Lou Dobbs, Fox Business Network anchor and one of Trump’s most obsequious cheerleaders, compared Romney to Judas. Right-wing Twitter was full of people bemoaning his betrayal. But here’s the thing, you can only betray something to which you owe your fealty.

Romney cannot betray the Republican Party because it is not a lord and he is not a vassal. Michael Wear, director of faith outreach for President Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign and author of Reclaiming Hope, said: “Political parties demand our loyalty not because it is their right, but because it is in their interest.” Political party members, whether they are Republican senators or my Bernie-or-bust next-door neighbor, are not machines. Pitch perfect performance of their party’s will is not proof of functionality. Instead, as Wear says, “We should be members of a political party because we believe things, we should not believe things because we are members of a political party.”

Over time, as automata became more convincing, philosophers sought to understand what truly separated finely wrought machines from the men (and women) who made them. From one century to the next, the answer has been either reason or a soul, or a soul which gives man reason. No matter the age or philosophy, the consensus is that there is something that animates mankind that does not inhabit machinekind. Automata do not have animus. Man may love a mechanism, but mechanisms can’t love man.

Romney cited his oath to God as the reason he felt obligated to vote to convict Trump. A love of God moves Mitt Romney. But it is not the love that can or should move each of us. Love is a well with many waters. We must learn to sit beside it again and see what springs forth.

We must stop imitating mechanical birds on hollow trees, singing out only when and how our party says we should. We are not metal devices crafted in the service of orthodoxy. We are soft-skinned, vein-threaded, blood-pumping men and women. I used to be afraid of disagreement. Over the past four years I have seen what it looks like when each side becomes increasingly exclusionary in its righteous certainty. I repent of every hope for rigid consensus.

It is an isolating time for the Democrat who believes dignity of life applies to the fetus growing in the womb, for the Republican who would lift the immigrant mother and her children over our borders and into a safe home. We cast them out, disgusted by their differences. Where are they to go, if they do not remain with us? What will we become without them? Dissonance can be resolved with the right harmony.

We must commit to love those who do not obey. To see those around us, even when they do not bend to our political will, as exceptionally well made. We must knock down the golden trees and stop winding up the trilling birds.

If we do not, if we cannot, we’ll be left with nothing but the wind-up gears of an imitation republic, automatically going through the motions of a liberal society but lacking the soul of one — a mere ceremonial room full of engineered display.