At Home with Anica Wong

An elegant dance in a utilitarian kitchen.

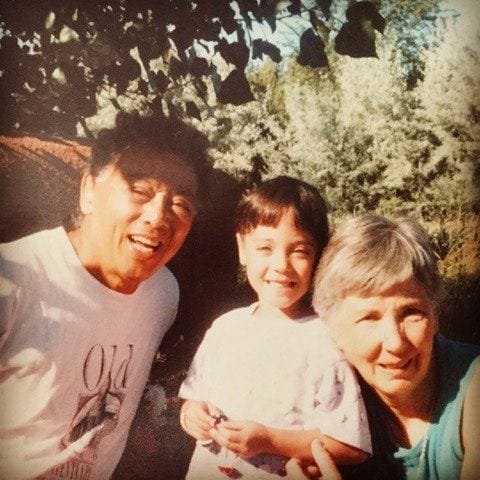

Anica Wong is a runner, reader and writer. She and her partner started an urban farm in the suburbs of Denver. They hope to use locally-grown produce to bring people together, heal the planet and live a richer life. Find Anica on Twitter. Find her urban farm, SoCliff Farm, on Instagram.

In this essay, Anica writes about two kitchens. Sitting with Anica in these spaces is sustaining. When I read this piece for the first time, I felt well-fed. You will too.

By Anica Wong

The carpet in Gramita’s kitchen was worn down to the white plastic threads in the spots where she stood the most — in front of the stove, the sink and the small slice of countertop that held the wooden breadbox, one of the two novelties of her tiny square kitchen. The other was a pull-out cutting board, which seemed like it contained a little bit of magic because it could get pushed back into its hiding spot.

My mom’s mom will always be known for making three things - Jello squares, biscochitos (a traditional New Mexican sugar cookie with a hint of anise) and tortillas. And that pull-out cutting board was critical in making the latter two. Because potatoes, apples, the aforementioned breadbox and toaster took up most of the precious counter space, Gramita used the cutting board for the real work in the kitchen. That’s where she rolled out the dough for biscochitos and used the heart, spade, diamond and club cookie cutters to make the shapes. They were then dipped into the cinnamon and sugar mix that gave them just enough sweetness to have you eating them by the dozen. Her biscochitos were best a day after they’d been baked and honestly, it wouldn’t be absurd if by the time you went to bed, you had lost count of how many you had actually eaten.

To make tortillas, the cutting board had to be dusted with flour so that the masa(dough) wouldn’t stick. Using the wooden rolling pin, she’d roll and rotate, roll and rotate the dough, bringing the tortilla to life with the flick of her wrists. As she stood on that threadbare spot, it was like her body had absorbed tortilla-making into her DNA; there was no wasted movement. It was an elegant dance in a utilitarian kitchen. Maybe that was why the pull-out cutting board had such an impact on me — it facilitated these amazing creations of hers and then, when done, was wiped off and pushed away, leaving space for the next order of business.

On my dad’s side, Gung Gung (grandfather in Cantonese) was as close to a master chef as I knew — he had cooked for his eight children for decades and continued to sustain his large extended family until he died. His kitchen felt alive! Oil pops from the wok, big cleaver chops and slammed stove doors created a cacophony - when you heard it, you knew you were going to eat good that night. Heck, you knew you were going to eat every night you were visiting my grandparents in Berkeley.

He, like Gramita, didn’t have a lot of counter space. He also didn’t have a breadbox but that didn’t stop us from visiting Acme Bread Company and picking up Pain d'Epi and cinnamon currant bread. The loaves in brown sacks would pile at the end of the counter, the Pain d’Epi waiting to get torn apart like leaves being picked off a stem, the cinnamon bread to be sliced, toasted and slathered with butter that was always at the ready on the counter’s return, never in the fridge.

And the crumbs from the bread, well, they were inevitable, especially with the crunchy bread. Those bits fell to the floor and most likely stayed in the spaces between the large black stones that were only found in the kitchen. Gung Gung and a friend had tiled and grouted the floor themselves, eons ago. Maybe they didn’t put enough grout. Or used the right kind to stand up to the wear and tear of a kitchen. Or maybe there had just been that many feet, walking and running, across the tiles that eventually, the grout was practically nonexistent. And so it seemed like the crumbs held the tile in place. There’s a metaphor in there, somewhere...that the little pieces of ourselves, the bits that feel like castoffs, are actually what hold the bigger chunks of life together.

My kitchen is very different from theirs. I don’t have a breadbox or a pull-out cutting board. The wooden floors get vacuumed every other day. And I haven’t lived in our house long enough to put a wear pattern in the rug in front of the sink. But it’s still a special place. I’m still creating memories there that get nestled alongside those of eating tortillas with Gramita and smelling the mingling of garlic and onions in Gung Gung’s kitchen. There is magic to be found in kitchens.