This is the first part of a three-part series on renting and home ownership in America. I am so looking forward to the discussion you and I are going to have around this. It’s beyond time.

Read the second part. Read the third part.

Every time someone new walked into a rental I called home, I apologized for it.

Hi, come in! It’s so nice to see you! Oh, don’t mind the floors, the paint, the cabinets, the windows, the appliances, the tile. This is just a rental. It’s not ummmmm, and then here a vague gesture with my hands, it’s not what I’d do if it were my own but, you know, anyways, how are you?

What did I mean “not my own”? Even the house I live in now, that I’ve purchased, isn’t really my own. It belongs to the bank. What did I expect from my guest in return when I knelt before them in abject horror over my linoleum and pressed wood countertops? Absolution because I was not currently a homeowner? Why, when I rented, did I feel like I need absolution? What sacred code did I feel I was transgressing when renting my home from a landlord instead of being in extreme debt to a mortgage company for it? Why was I ashamed?

To find the source of a current shame, we need to understand the centuries that preceded it and produced it. The western world was obsessed with private property long before the medieval feudal system. But since the Middle Ages seems far enough back to begin to understand my shame, let’s start there. You remember feudalism, right? “What was the feudal system?” was definitely a question on your 11th grade history test.

In case you’ve forgotten, feudalism was a medieval system of governance that structured society around who owned land and who did not. A warrior class of landholders - given their estates by the Crown - provided military protection to the tenants on their land. This protection wasn't free. It cost the tenants labor on the land, loyalty and a hearty portion of their crops. Tenants always had to pay up and often went hungry. Landlords, I mean ahem, landholders only sometimes protected their tenants. They were always well-fed.

Feudalism was the social system of numerous civilizations at numerous points of medieval history. The decentralization of an empire usually occurred came before it became feudal. Local control and protection became important when empire-wide unified control and protection dissolved. Absent state protection of common citizens, private property becomes a tool used by individuals to control their fellow citizens. That doesn’t sound like something that happens in your average American neighborhood, does it? Ahem. (Sorry, be right back, I need to go sip some tea after writing that sentence.)

In the centuries after feudalism, development helped empires regain centralized control. Feudalism disappeared but property ownership as a means to control people didn’t. There are too many examples! Like!

Enclosure - the British government-sanctioned practice of taking common land that sustained entire communities, deeding it to private owners and fencing it off. America stealing land from its indigenous original occupants, forcing them onto reservations and deeding their land to private owners. Tying voting rights to property ownership. As does the fact that in America it took decades of legislation in the 1800s to grant women the right to own land.

Now, we look at these abuses of community through property ownership and shake our heads! Property ownership is a human right! And is available to everyone! And we know this because we’ve been taught it’s a part of the American Dream! And the American Dream belongs to everyone! But ummmm…

Friends, take a seat. This next part is bumpy.

The American Dream has been around in various forms for a long time. Owning your own home has only really been a part of it since just after World War II. There were a lot of factors at play. But one of the most impactful was a McCarthy era fear of Communism. During WWII, America invested in public housing projects for servicemen and their families. The experiment had gone well and was expanding.

Katy Kelleher writes in Curbed, “In the 1940s, McCarthy and other right-wing politicians became concerned that the housing projects had gone too far — McCarthy even called public housing ‘breeding ground[s] for communists.’” They pushed the government to “shift its focus from providing housing for those in need to providing mortgage assistance.” This push led to the birth of the suburbs, with their rows of single-family homes, along the financing model that made them possible.

Why would home ownership fight communism? They thought that someone who literally bought into America would be more committed to American ideals. I can see how this buy-in idea makes sense if you’re looking to inspire loyalty to an enterprise.

When I was eight, my grandparents gave me one single share in Disney stock. It came with a stock certificate. I got a yearly report in the mail telling me what my stock was worth. I spent much of my childhood feeling that I had a real stake in Disney’s success. When I went to Disneyland, I’d try to guess which brick was mine. Surely my stock meant I really owned a part of Disneyland! Every corporate success was my success too. Every failure threatened my holding. When ten-year-old me saw a news story about how Disneyland Paris was floundering, I thought, “Gosh, could they make better decisions? I’ve got a stock with them!”

It’s been a long time since I thought that stock certificate meant anything; it’s moldering somewhere in the bottom of a box in storage. And, despite Walt Disney’s original compelling vision, I no longer feel any loyalty to the ideals of that particular enterprise. (Their casualness about human rights abuses certainly hasn’t helped.) My single stock, and the illusion of ownership it gave me, explains why we’ve allowed home ownership to work as a signifier of social stakeholding.

We’ve agreed with McCarthy that home ownership is proof that you’ve bought into the American project. Even with equal access to home ownership this attitude would be grossly unfair and grossly, well, gross. But we don’t have equal access in America. We spent most of the 20th century intentionally engineering systems that gave some people access to home ownership while denying access to others.

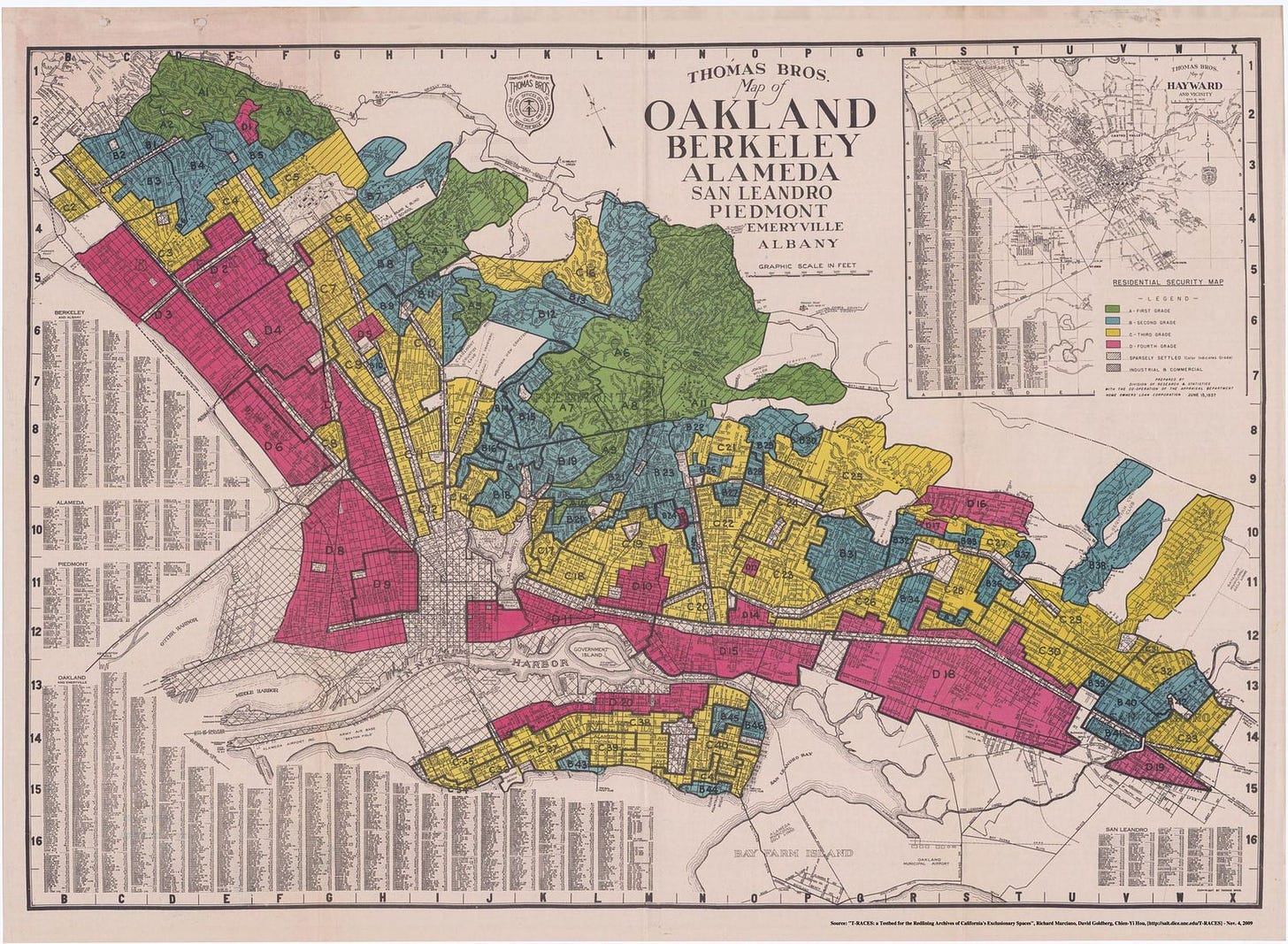

Ever heard of redlining? In 1935, a government agency called the Federal Home Loan Bank Board commissioned “residential security maps” in 239 cities. The maps claimed to depict how secure real-estate investments were in each city. They were used by every bank in the cities covered.

The maps determined who got loans and who did not in an official capacity for decades. Areas in each city were ranked from Type A to Type D. Type A areas were considered “desirable” and loan-friendly. Type B and C were ranked, “Still desirable” and “Declining”, respectively. Type D areas - outlined in red - were considered too risky for home loan access. Type A neighborhoods were traditionally white and Type D neighborhoods were traditionally Black.

If you lived in a Type D neighborhood, it was nearly impossible to get a loan. Each map was drawn with the express purpose of keeping Black Americans from owning their own homes.

Redlining created a housing market founded on racial segregation. It gave white people the cover of the free market competition as the excuse for their all white neighborhoods and all white schools. With homeownership as a prerequisite for stakeholder status, Black people were denied a voice as stakeholders in their own neighborhoods. Home ownership is America's most common, effective wealth building instrument. When Black people were denied homeownership, they were denied upward social mobility. Were? Are.

Redlining is illegal now but still happens with home loans and appraisals. And white people are still benefiting from it. Drive through the flats of Oakland - a place deemed Type D in 1935 and coded in red - and every flipped house is a testament to this continued advantage. White home buyers and corporate developers buy properties in communities where people could not get a home loan, or could only secure one at exorbitant default-ready rates. Many of the people who were raised in these communities are being forced out. With the American Dream of home ownership long denied them, they now cannot afford rent in their own hometowns.

Home loans weren’t the only way to control community through private property. In the 20th century, some house deeds dictated the race of the person who could purchase the home. They also sometimes determined what race of person could visit the home and for how long. One deed for a Hollywood Hills home said, “no one of African or Asiatic descent could remain on the property after 6 p.m., unless that individual was a caregiver to someone living in the home.” Written in the 1920s, it was enforced for decades afterwards.

The current owners of the house, a Filipino man and his husband, would not have been able to live in it during much of the 20th century. I’ve rented in neighborhoods built with early 20th century covenants excluding anyone who wasn't white from purchasing within their boundaries. The covenants are gone but those neighborhoods are still segregated today.

From feudalism to the American Dream, there are quite a few sources for my particular western embarrassment. When I’ve opened the door to a home I was renting and felt ashamed, I was burdened by centuries of classist, racist, xenophobic, misogynistic legal codes, traditions and attitudes.

Of course, as a white woman this heritage is far less burdensome to me than it is to many, many other people. As a white woman in this time and place, in addition to being burdened by this heritage, I can also buy into it. While most of my ancestors were too poor to own private property, pro-home ownership policies (for white people!) in the 20th century paved the way for Riley and I (white people!) to buy a home in the 21st century.

So now, my old shame is replaced with a new one. This shame, I can source immediately. It’s the shame of someone who bought into this version of the American dream uncritically and at an excellent interest rate. With my name on the mortgage and the bank’s name on the deed to our house, the question must be asked,

Is home ownership a moldering American stock certificate in the bottom of a box?

Read the second part. Read the third part.